The Bicycle: Evolution or Intelligent Design. Part II

Mon, December 1, 2014

Mon, December 1, 2014

This is Part II of a three part series, If you haven’t already read Part I, you can read it here.

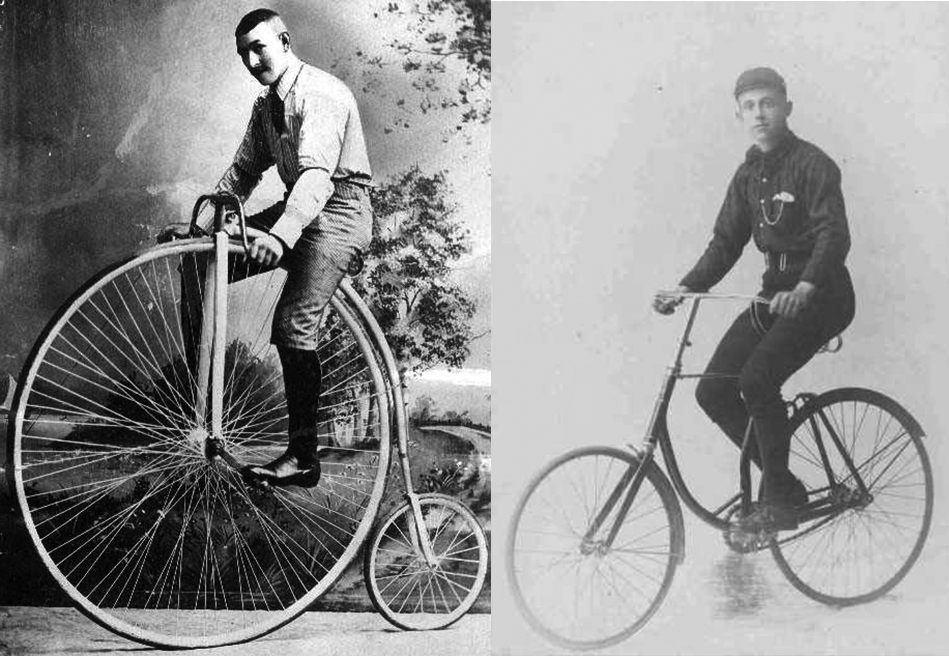

Soon after the chain driven bicycle was invented in 1885, a whole bicycle industry sprang up in Britain. Bicycles were mass produced, making them affordable for the working man. For the next 60 years the bicycle became the working man’s form of transport. And bicycle racing the working man’s sport.

Because Britain was the first to industrialize bicycle manufacture, certain standards were set, and the rest of the world followed. The half an inch pitch bicycle chain is a good example, it is still the standard today worldwide, even in countries that have always used the metric system of measurement.

Bicycle frame tubes were a standard 1 1/8 inch seat and down tubes, 1 inch top tube, 1 1/4 inch head tube. With the exception of the French who used metric size tubes, most of the rest of the world used the Standard English size tubes, even the Italians. And this would remain the standard, especially for lightweight racing frames for almost 100 years.

The horizontal, level top tube became standard. It was the framebuilder’s point of reference. All other angles were measured off the top tube, it was parallel to a line drawn though the wheel centers. (Assuming both wheel are the same size.)

Traditionally, lightweight frames were custom built, one at a time. My mentor, Pop Hodge, would assemble a frame, measure all the angles and tube lengths. Then lay it out on the brick floor of his shop. The top tube would line up with the edge of a row of bricks. There were marks scratched into the bricks where the Bottom Bracket should be, the same with the rear drop-outs, the bottom head lug, etc.

He would then drill a hole with a hand cranked drill, (He used no power tools.) and pin the tubes in the lugs with a penny nail. (A penny nail was a reference to its size.) When the whole frame was assembled, he would place it in a hearth of hot coals, (Again with a hand cranked blower.) Heat the whole joint to a light red heat, when he would feed in the brass, and braze the joint.

The first framebuilders were blacksmiths, and Pop Hodge had been building frames since 1907 built in that traditional way. He had a hand held torch that he used to add braze-ons and other small parts. It burned coal gas, from the town’s supply that was piped in to all homes and businesses for cooking and heating. The flame was boosted by foot operated air bellows.

The level top tube also had the advantage that once a person established what size frame suited them, any make of frame in that same size would fit. Even though seat angles, and top tube lengths may vary, it would only be slight and could be taken care of with a longer or shorter handlebar stem.

The main reason different makes of frames worked as long as the frame size was the same. When the saddle was set at the correct height, and the handlebars would then be automatically the correct height in relation to the top of the saddle. No one spoke of “Handlebar Drop,” it was an unnecessary measurement, as long as the top tube was level.

In the late 1950s and through the 1960s there was a huge social change taking place in the UK and the rest of Europe. Economies were booming, (Because of the WWII recovery.) and the working man was buying a car for the first time. My parents never owned or even learned to drive a car, but the younger generations were abandoning their bicycles and buying a car.

Even the racing cyclists, mostly owned one bike. They rode to work on it, which was a big part of their training. On the weekends, the fenders (Mudguards.) and saddle bag came off, racing wheels were fitted, and a time-trial was ridden.

For many cyclists, Time-Trialing in the UK in the 1950s and before was more a social event than a serious athletic event. Owning a car for the first time changed the whole social structure of the working man, and many gave up cycling completely.

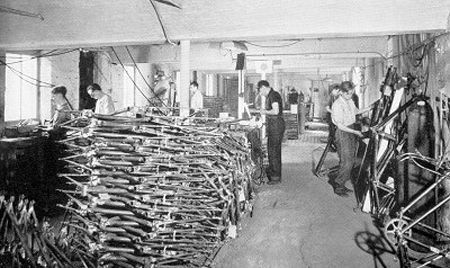

The result was a huge slump in the bicycle business at all levels. Prices of lightweight frames remained stagnant for many years and framebuilders had to look to ways to cut costs. The ones who survived were the ones who moved away from building frames one at a time, and managed to produce large numbers of frames sold at a reasonable price. See top picture.

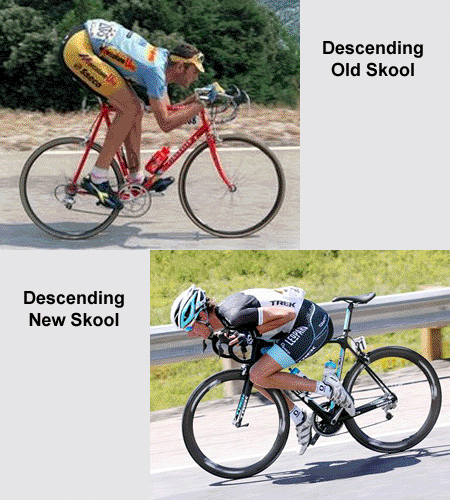

I mentioned in Part I of this series, that the standard racing frame geometry of that era was 71 degree seat angle, 73 head. To simplify the design the parallel frame was introduced, that is one where the head and seat angles are the same.

People were not ready to make a big jump from 71 to 73 degree seat angle, so a compromise was made and the 72 degree parallel frame was introduced. Advertised as a “Massed Start” or Road Racing Frame, the parallel frame had the advantage that a complete range of sizes could be made using only two, maybe three top tube lengths.

Simple jigs were used to assemble the frames, the same length top tube could be slid up or down between the parallel head and seat tubes, to build several different size frames. Maybe not the ideal set up, but it did cut the cost of building frames, and as I mentioned before the reach could be adjusted with a different length stem.

Tubes could be pre-mitered using the same angles, another time saver. By the mid-1960s the parallel frame concept was accepted by most people, and the 73 degree parallel became the norm. 73 was a better head angle, and riders soon found that the 73 degree seat was better too. Less tendency to slide forward on the saddle.

So once again here was a trend started by framebuilders because it suited them, but actually lead to a better riding bike. This series will have to run into a third part. Next I will touch on the steep head angle trend of the 1970s and how that came about, and then bring the story up to the present day.

To Share click "Share Article" below

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |