Joe Cirone

Mon, October 31, 2022

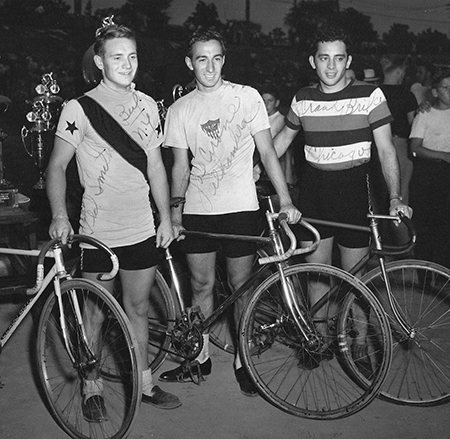

Mon, October 31, 2022  I was recently contacted by Joe Cirone, (Left.) who lives in Visalia, CA. Joe is now 92 years old and raced bikes, with success back in the late 1940s early 1950s.

I was recently contacted by Joe Cirone, (Left.) who lives in Visalia, CA. Joe is now 92 years old and raced bikes, with success back in the late 1940s early 1950s.

Joe Cirone has been corresponding with me since 2006, when he told me about a frame he had built in the winter of 1948. The builder’s name was Mike Moulton, same name as me, but not related as far as I know.

Mike Moulton, from Tujunga, California, was an engineer for the Lockheed Aircraft Company. He built bike frames as a hobby.in a little workshop at the back of his house.

I can imagine back in the late 1940s, early 1950s, cycle racing was somewhat a “Cinderella” sport in America, and one could not easily find a track frame in the US. So, to find someone locally with the necessary skill to build such a frame must have been rare.

More about Mike Moulton later, but getting back to Joe Cirone, he got into bike racing in 1946 and found that he was a pretty good at it when he won the Junior National Championship in 1947.

Joe Cirone leads in a 1000 m. Match Sprint. 1948 US Nat. Championship.Joe tried out for the Olympic Team in 1948 but fell short by a little over one second in the 1000 meter Time Trial, held in Milwaukee Wisconsin. He did however take 2nd in the Nationals Senior Championship that year held in Kenosha Wisc.

Joe Cirone leads in a 1000 m. Match Sprint. 1948 US Nat. Championship.Joe tried out for the Olympic Team in 1948 but fell short by a little over one second in the 1000 meter Time Trial, held in Milwaukee Wisconsin. He did however take 2nd in the Nationals Senior Championship that year held in Kenosha Wisc.

It was when Joe Cirone returned home to California in 1948, he met Mike Moulton at one of the races held in Pasadena and Mike offered to build him a frame. Joe rode that bike to the end of his career, and still owns it to this day.

1948 US Nat. Championships. Joe Cirone center.In 1951 Joe was part of a "Special American Team" that went to Japan on a "Good Will" Tour for one month. He raced against Japanese Teams up and down Japan. The team averaged two races each week, ending in a Special Event in Tokyo Stadium.

1948 US Nat. Championships. Joe Cirone center.In 1951 Joe was part of a "Special American Team" that went to Japan on a "Good Will" Tour for one month. He raced against Japanese Teams up and down Japan. The team averaged two races each week, ending in a Special Event in Tokyo Stadium.

Before he left Japan, a large Japanese Bike Manufacturer offered Joe $1,000 for his bike. A great deal of money back then, but Joe turned the offer down a kept his beloved bike. The same bike he holds in the picture at the top of thes article.

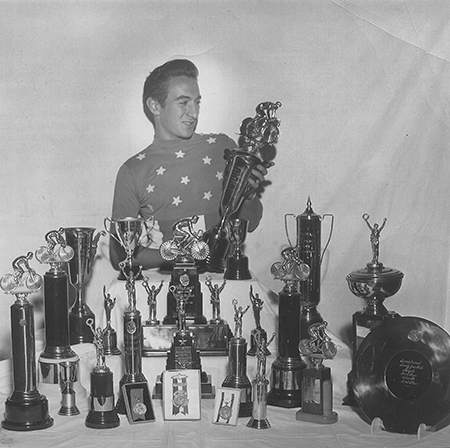

Joe Cirone with his collection of Trophies.Some links to previous articles:

Joe Cirone with his collection of Trophies.Some links to previous articles:

Later that same year, (2007) I wrote a follow up.

In 2013 I learned of another Mike Moulton track frame that had been nicely restored.

More pictures of Joe Cirone's buike built by Mike Moulton.

Foot note: Don’t confuse Mike Moulton with Mike Melton, another fine American builder.