Frame Design: Then and Now

Mon, March 12, 2012

Mon, March 12, 2012

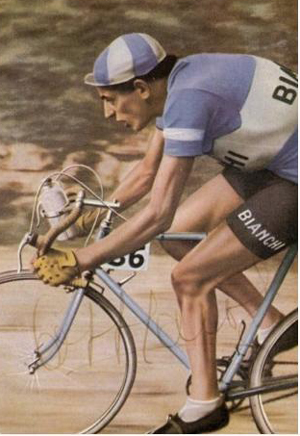

The above picture is me riding in the British National 12 Hour TT Championship in 1953; dating the picture is the spare tubular tire worn around my shoulders as the pros did in that era.

My bike frame size back then was 22 inch; (56cm.) compare that to the 51cm. I rode at the end of my racing career in the early 1980s, and still ride today. That is a whapping 5cm or 2 inches smaller.

If I rode a 56cm. frame today it would way too big for me, and yet looking at the above picture my bike looks fine and not too large at all. So what happened; did I shrink over the years? I was certainly a lot slimmer back in my youth, but my legs are pretty much the same length as they are now.

A clue is in the amount of seat post showing; about 2.5 inches (6.3cm.) in the above picture; I have 4.5 inches (11.4cm.) on my current bike. This accounts for the 2 inch (50cm.) difference in frame size.

The reason my 1953 bike does not appear too big for me is because it wasn’t; it was a totally different design than today’s frame. My bottom bracket height was only 9.25 inches; (23.5cm.) today’s bike has a BB height of 10.625 inches (27cm.)

I would also point out that all racing cyclists in the 1950s, including the pros, pedaled much lower gears, sat more upright, and rode with their saddles set lower by today’s standard.

I would also point out that all racing cyclists in the 1950s, including the pros, pedaled much lower gears, sat more upright, and rode with their saddles set lower by today’s standard.

See picture of Fausto Coppi on right.

I can remember that my bottom bracket was low enough that I could lower my heel and actually touch the ground.

Our cycling shoes had real leather soles, and had steel tips on the heels to prevent wear when walking.

While out training after dark, and coasting down hill; we would sometimes lower our heel so the steel tip made contact with the road, sending out a shower of sparks. A pretty spectacular visual effect, especially if several riders did it together.

When you lower the bottom bracket on a frame you also lower everything above it, the top tube and the height of the saddle from the ground. You do not necessarily lower the saddle in relation to the pedals. That will be whatever the rider sets it at.

However, the handlebars are not lowered by as much. The reason being that the size of the front wheel and therefore the length of the front fork are constant no matter what frame size. Above the front fork there is a head tube and head bearings.

It would be impossible to build a 51cm. frame with a nine and a quarter inch BB height, because with a level top tube there would be no room for a head tube; which is why I rode a much larger frame back then. Or not so much a larger frame, but one with a lower BB and a longer seat tube.

Over the years the bottom bracket height on racing frames has increased; not because striking a pedal on the ground was an issue. (I never found it to be a problem.) But rather one of making the BB higher makes the chainstays and down tube shorter, and therefore makes a stiffer frame.

Also probably the main factor driving frame design is the change in riding positions of today’s racing cyclists, over those of their predecessors in the 1950s. I have already mentioned the 50s riders sat more upright because the handlebars were higher in relation to the saddle.

Today’s racing bicycle has a large saddle to handlebar height difference; which is how most racing frames sold today are designed. However, the majority of the frames are bought by non raciing leisure riders; using them purely for exercise and pleasure riding. Many of them like myself are older, and are not flexible enough to get down in those horizontal, low tuck racing positions.

Today’s frame design with its sloping top tube does not restrict a frame designer/builder like the level top tube did. No matter what the BB height and seat tube length, the head tube can be any length. So anyone having a frame built for leisure riding by an independent builder might consider lowering the BB height.

I did this when drawing up the specs for my New Fuso that Russ Denny is building for me. This is probably the last frame I will ever need. I designed it with an 8.5cm. drop; which is a 10 inch. (25.3cm.) BB height. (Drawing below.)

This does two things; by sitting closer to the ground it will be easier to put my foot down when stopping. But more importantly, a lower bottom bracket means the saddle is lower in relation to both the ground and the handlebars.

Not the other way round of having the seat high to begin with, then raising the handlebars to achieve the desired position.

I have come to realize, the racing position of the 1950s is probably the ideal leisure riding position for today. I will have my frame built lug-less; (Welded.) this means there is no restriction on angles, and because the modern design has a sloping top tube it is no longer necessary that I go to a larger frame.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |  Bicycle Design,

Bicycle Design,  Bike Fit,

Bike Fit,  Bike Tech,

Bike Tech,  Fuso

Fuso