The Evolution of Frame Design. Part I: The Wheelbarrow Effect

Mon, October 5, 2009

Mon, October 5, 2009

The picture above is Italian cyclist Giuseppe Martano, seen here on his ride to 2nd place in the 1934 Tour de France.

Probably the first thing most will notice is that the bike has a single fixed sprocket. Gears were available at that time; however, Tour de France riders were restricted to a single speed at the whim of Tour organizer Henri Desgrange.

Desgrange felt that multiple gears were for bicycle tourists, and they took away from the purity of the sport of cycle racing. So riders had to struggle over the same mountain climbs the Tour currently goes over, with a single gear, on roads in far worse condition than today.

The other thing you will notice about the bike is the long wheelbase, some 4 or 5 inches (10 to 13cm.) longer than a modern race bike, the shallow frame angles, and the long curved front fork blades.

One of the reasons for the long fork rake or offset, was always thought to be because roads were so bad back then; in most European countries little more than dirt roads.

One of the reasons for the long fork rake or offset, was always thought to be because roads were so bad back then; in most European countries little more than dirt roads.

The long curve of the fork would allow the fork to flex acting somewhat as a form of suspension.

However, there was another reason; a long held theory that trail made the steering sluggish on a bicycle.

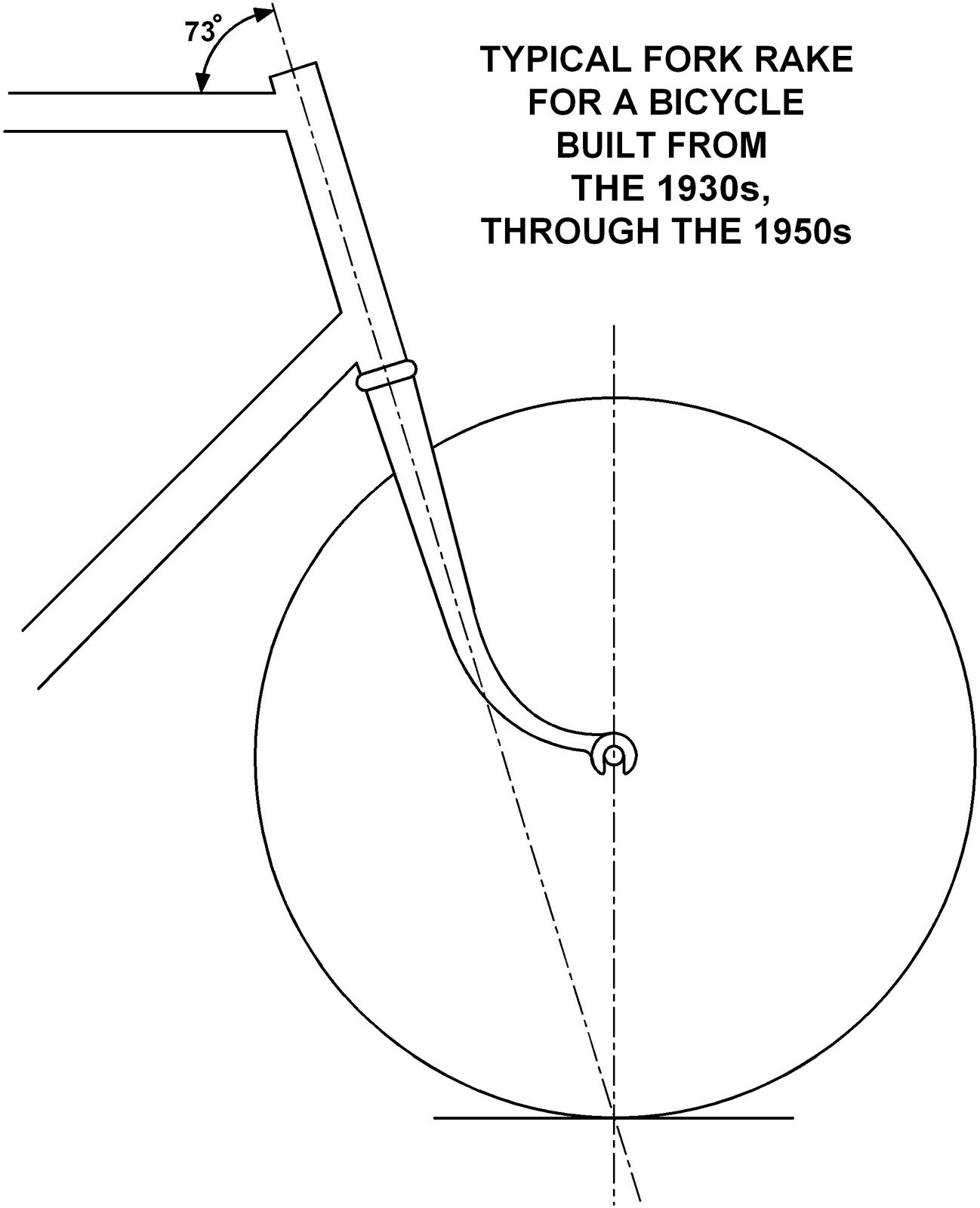

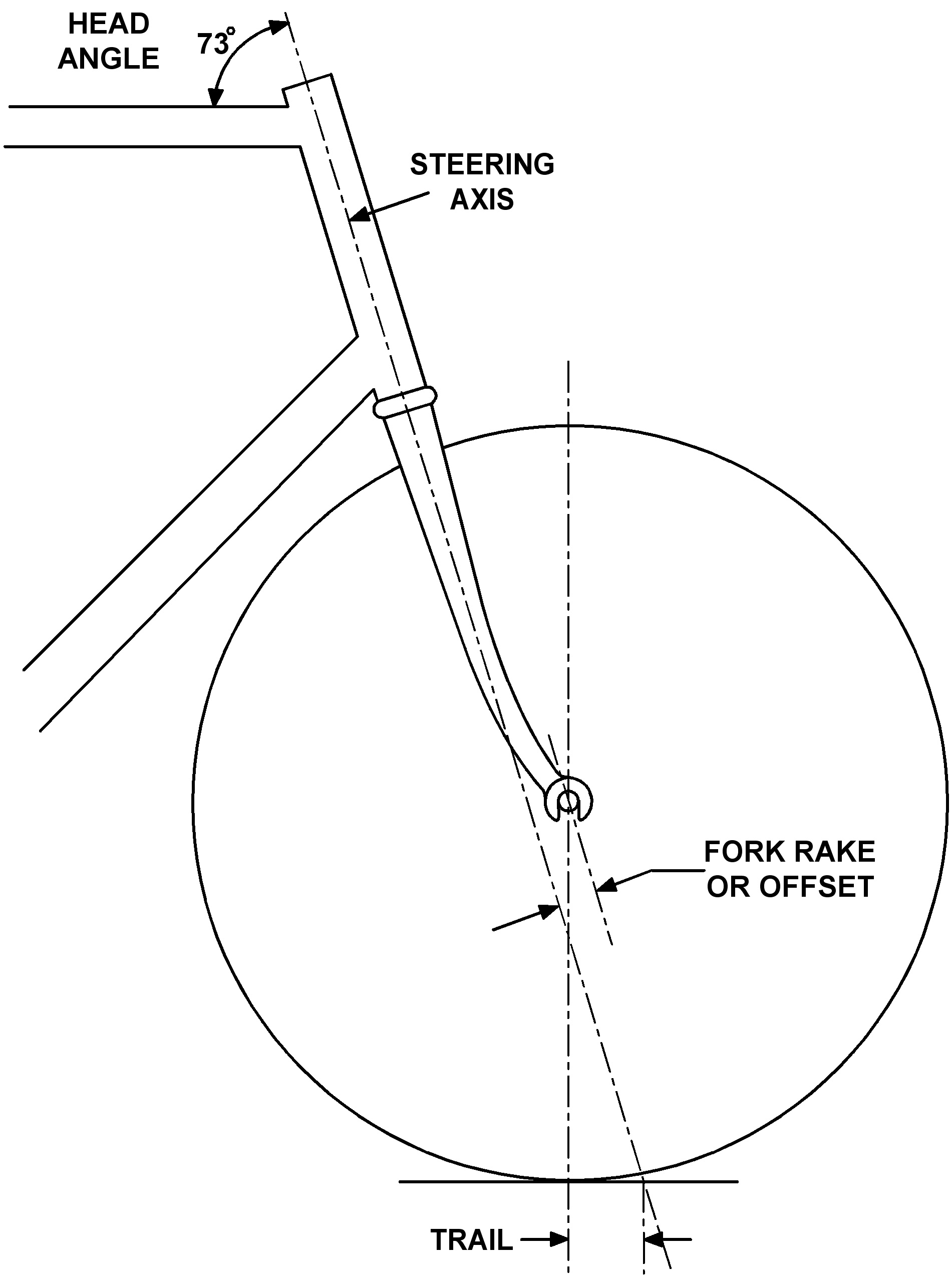

If you look at the drawing (Above left.) an imaginary line through the center of the head tube, (Steering Axis.) reaches the ground at the point of contact. On a bike from this era, there was zero trail.

On a modern bike (Drawing right.) the point where the wheel contacts the road will be some 2 to 2.5 inches (5 to 6.3cm.) behind the steering axis.

On a modern bike (Drawing right.) the point where the wheel contacts the road will be some 2 to 2.5 inches (5 to 6.3cm.) behind the steering axis.

Hence the term “Trail,” because the wheel trails along behind the steering axis.

Bicycle geometry did not change much from the 1930s until the 1950s when I started racing.

Standard road frame angles were 71 degree seat angle, and 73 degree head angle. This was true for any size frame.

Frame lugs were heavy steel castings, machined on the inside to accept the tubes at these standard angles. It was not cost affective to make lugs in different varying angles. It was established probably around the 1930s that 73 degrees was the ideal head angle for a road bicycle; this is still true today.

The reason for the seat angle being 2 degrees shallower was because when a framebuilder made a larger frame, the top tube became longer because the head and seat tubes were diverging away from each other.

These standard angles were not for the benefit of the rider, but for ease of construction for the framebuilder.

For a shorter rider like myself, the top tube was always too long and I was sitting back too far.

When I made maximum effort I always found myself sliding forward and sitting on the nose of the saddle. As well as being uncomfortable, it had the effect of the saddle being too low.

Because of the long top tube, I always had to use a short handlebar stem, and this lead to another problem when sprinting or climbing out of the saddle.

The rider’s weight was behind the front wheel’s contact point with the road; due to the short stem and the forward sweeping forks. Out of the saddle, the bike swung from side to side in an arc causing the front wheel to steer first one way then the other; not holding a straight line.

At the same time the gyroscopic action of the spinning wheel was trying to keep on a straight line. So the two actions were fighting each other; hence the bike felt sluggish and unstable.

To demonstrate this effect to yourself; hold a pen or ruler on a table top at 90 degrees to the surface, and move from side to side keeping the point of the pen in one spot; you are moving in one plane. Now hold the pen at an angle of 45 degrees and move from side to side and you will see that you swing in an arc.

This was something I later called the “Wheelbarrow Effect.” In Part II I will talk about how frame design evolved through the 1960s and 1970s to arrive closer to what we see today.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Reader Comments (8)

Thanks for the succinct and clear description of "trail," a term which I've seen mentioned a lot lately but didn't understand. The excellent diagrams helped a lot.

An excellent post Dave. I really enjoy reading your insights on frame design, particularly from a historical perspective.

I have read the explanation of trail many times but only now truly grasped it.

My 1963 Carpenter's Rudd forks had a similar rake to diagram 1. The steering flopped around when climbing hills. Then Tom Board, who was making some mods to the frame, cut about 20 mm off the forktips. I thought this was a bit radical but the bike rode a lot better after that.

Dave is back and I love it! Education and knowledge is preferred to non-ending debates regarding infrastructure, new products, etc. The weight balance issue is one matter I constantly think about and test when riding... look forward to more.

Dave is on the money on frame design. I don't know if the Bicycling magazine review of the Fuso, circa 1986 is available online but it surmises what Dave has done very well. I have a copy of that review buried away along with all of my paperwork for my Fuso. To quote but one line, it said "the bike corners as though it were on rails." Geometry plays into not only how a bike handles but how it is either enjoyed or despised by the rider.

I was fairly sure I wanted the Fuso but before I made my decision, I test rode just about everything on the market. Mind you, I was a roadie with a dabbling in track (kilo). I tested criterium bikes, road bikes, and even tried a touring bike or two just for kicks. The steeper angles of a crit bike made for more agile handling but the shallower angles of a road frame meant that a longer race wouldn't wear you out just trying to stay atop the bike. Liken the difference between a cutting horse and a pleasure horse.

Finally, while Dave made the decision for a bike of his design easy, he also made it a hell by offering a choice of colours and colour combinations. You just don't get that off the shelf. I spent more time choosing the colour than I did choosing the framebuilder. I'm looking forward to more design insights in the future. BTW, the Fuso isn't for sale!

Great stuff, Dave. I'd be very interested to hear your regarded opinion on the French-style "randoneusse" bikes built with minimal trail for front-loading, e.g. to accommodate rack, decaleur and Gilles Berthoud-type bag.

Like this: http://www.veloweb.ca/garagepages/vo_rackinstall.html

Does it make sense to you to build low trail for specific front-loading?

Hello Dave

Thanks for all the good stuff you write about … and for not letting the left-field posters who visit your blog put you off writing some more.

We want to present you with a design query, to settle (or inflame) a current debate. Firstly (anticipating receiving posts from the same ‘experts’ who challenged your ‘out of the box’ statement at the end of your excellent 3-part series) we wish to qualify our position, we are a design team that just achieved World Championship success in Mendrisio.

The attached file provides some insight into what we believe could be the ‘next big thing’ in bicycle design, ‘seat integrated design’, with the correct ‘seat’ being integrated into each bike’s design from the outset of the design process, instead of the present practice of making ‘saddle selection’ the last item on the design agenda.

If we are right, then the rider will remain in the one position on the ‘seat’ for much longer periods than in the past, to continue receiving correct support.

Now ... the question.. what implications do you feel there are for the rider remaining in the same position for most of the ride ? (applied to road seat… not the other model seat)

laterelle.com

Thank you for your thoughts.

Laterelle

contact@laterelle.com

i think “Wheelbarrow Effect” it's because of the rake in the fork, the bigger the rake, the more “Wheelbarrow Effect”; and not because the wheel being more in front of the rider. because when you sprint you pull the bike from the side-right (lets say) to up-vertical to the side-left. in the first phase, from the side to up everything it's okay because you place the hands firmly on the handlebar, especially the right in our case. then when you put the bike to the other side, the last part of this motion has some moment of relaxation coming from you; but this last part caries the biggest momentum from the bike, especially from the front wheel. because the wheel along the steering axle is more to one side (front, because of the rake in the fork) than the other it will start to move, and the big part will have more weight, more inertia, thus the front wheel will tend to steer by it self.