When some one sent me a picture of a Fuso bike, (Above.) I knew at first glance that I did not build it. This one was built by Russ Denny, my former apprentice who took over my business when I retired in 1993. The frame had a sloping top tube, and while this is normal today, back prior to 1993 it was not.

I never built any frame with anything but a level top tube, with the exception of a few drop top ladies model, and the occasional twin tube “Mixtie” frame, which is a whole different frame design. I m talking of the standard road frame.

It made me think, what a run this simple design had. From the early 1900s until the mid to late 1990s, almost made it a hundred years without any major changes. Apart from basic geometry, tube angles, etc., once the standards were established, they remained the same, a level top tube was one of them, and any deviation from that was not acceptable, to either the framebuilder or the customer.

What I find amazing is that everything else changed so dramatically over the same period, I think of automobiles, aircraft, and just about any other manufactured item. They have all been though many changes over the same period.

It all started with the invention of the chain drive. The first was the British model “Rover” Safety Bicycle.So-called because its fore-runner was the Ordinary or High-wheeler model, (Below right,)

It all started with the invention of the chain drive. The first was the British model “Rover” Safety Bicycle.So-called because its fore-runner was the Ordinary or High-wheeler model, (Below right,)

Although this was the first “Enthusiasts” bike, one had to be young, athletic, and have nerves of steel to even mount such a machine.

The Rover design pretty much established that the chain would drive the rear wheel, while the front wheel would provide a means of steering. The chainwheel, cranks and pedals would be just ahead of the rear wheel, and below the rider’s saddle.

The Rover design pretty much established that the chain would drive the rear wheel, while the front wheel would provide a means of steering. The chainwheel, cranks and pedals would be just ahead of the rear wheel, and below the rider’s saddle.

The rider’s position was copied from the ordinary, and lead to those early frames having laid back “Slack” frame angles that would prevail into the 1950s.

Early frames were a hodge-podge of tubes of various shapes and sizes. The bicycle soon became mass-produced, which lead to it becoming an affordable means of transport for the working classes. Prior to that the only personal form of transport was a horse,

Mass production also lead to standard-ization and simplification of design. The chain itself is still half an inch pitch today the whole world over, even though most countries use the metric system.

Mass production also lead to standard-ization and simplification of design. The chain itself is still half an inch pitch today the whole world over, even though most countries use the metric system.

Wheel sizes became standardized, and the frame design became the simple straight tube, diamond design, that we are all so familiar with.

Most of these standardizations came within the first ten years into the early 1900s. Tube sizes, 1 ¼ Head tube, 1 1/8th. Down and seat tube, 1-inch top tube. Most countries in the world including Italy, use these same Imperial size tubes. Hand brazed, lugged steel frames were, for the most part, the norm throughout this period.

It soon became obvious that frames would have to be different sizes to accommodate different size people, and the level top tube being parallel to the wheel centers, made it a point of reference, for the framebuilder to easily design and build a frame of any size.

It soon became obvious that frames would have to be different sizes to accommodate different size people, and the level top tube being parallel to the wheel centers, made it a point of reference, for the framebuilder to easily design and build a frame of any size.

The front fork being the same height for any frame, the position of the bottom head lug, and the length of the head tube is easy to arrive at, and head and seat angles are measured from horizontal top tube.

The advantage for the customer was, once he had established a size of frame that suited him, he could buy another of any make in that size, and it would fit.

Plus, the handlebars would be the correct height in relation to the saddle. No one spoke of handlebar drop.

When I left England in the late 1970s, my customers were almost exclusively amateur racing cyclists, their bikes all had the same componentry. Campagnolo Group, Cinelli handlebars and stem. Christophe toe clips, Binda laminated toe-straps. Tubular tires, and usually Mavic rims. Frames were either by a local builder like me, and therefore varied from one area to another.

If the frame was not by a local builder, it was by one of the larger English builders. Holdsworth, Mercian, Jack Taylor. Italian frames were not big in England at the time. They were expensive compared to the UK built frames.

When the US Bike Boom happened in the 1970s English framebuilders, even the larger ones could not supply the demand, and they lost out to the Italian companies that were larger, as they had been supplying most of the continent of Europe for years.

By moving to America, I was able to compete for a small niche of the market, but when the second bike boom hit, namely the Mountain Bike craze. Only a few high-end established mountain bike specialists were able to take advantage of their particular niche. The rest was taken over by companies like Giant, who found by building frames with sloping top tubes, they were able to build less sizes.

Above illusrates the evolution from the "One size fits all" BMX Bike, to the limited size MTB and Road Bike.

When this look became the norm, it made its way to road bikes, and by then carbon fiber was taking over from steel. Lugged steel had a good run, and I am proud to have been around at the end of that era.

The only other products I can think of that are made by craftsmen and remain the same year after year, are musical instruments. Everything else, including bicycles are now the same as any other consumer product that can become obsolete at the whim of the manufacturer.

The bicycle, and in particular the lugged steel racing bike, took about ten years to establish standard designs and practices that would last for another 90 years. Towards the end changes in componentry came at a fast pace, (Index shifting, clipless pedals, etc.) culminating in the demise of the frame itself, which is fitting because after all the frame is the heart and soul of the bicycle.

To Share click "Share Article" below

To Share click "Share Article" below

Mon, December 13, 2021

Mon, December 13, 2021

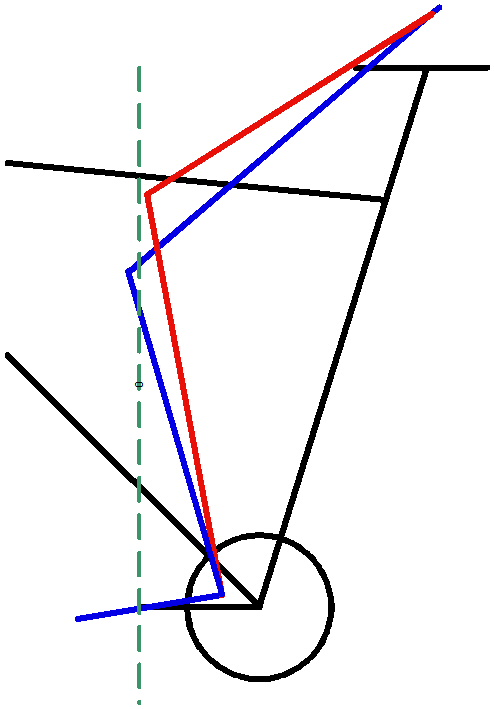

If you look at the drawing on the left, you can visualize that a smaller wheel means less trail, a steeper head angle also means less trail, but the reverse fork increases trail to compensate. A stayer bike may have a little more trail than the average track bike, but not an excessive amount.

If you look at the drawing on the left, you can visualize that a smaller wheel means less trail, a steeper head angle also means less trail, but the reverse fork increases trail to compensate. A stayer bike may have a little more trail than the average track bike, but not an excessive amount. To Share click "Share Article" below

To Share click "Share Article" below