Weight Distribution

Tue, April 2, 2013

Tue, April 2, 2013

It was pointed out to me recently that of all the articles I had written about bicycle design, I had not written one about weight distribution.

It is a subject that while somewhat important, it is not as important as a good riding position, and once a frame or bike is built and the rider has set it up to his or her absolute best position, are they then going to alter that position to achieve a certain weight distribution? That would be counter productive.

The rider is the engine that propels the bike forward, and a proper riding position is of the utmost importance for the body to work at maximum efficiency. I am talking of the racing cyclist who is looking to get optimum performance from body and machine.

If you are riding for leisure or exercise, you may sacrifice some efficiency for comfort, especially if you are older or not in top physical condition. You will adjust your riding position accordingly and weight distribution is probably not important enough to be even thinking about.

Under normal riding conditions there is always be more weight on the rear wheel that the front, simply because of the mass of the rider’s weight is behind the center point between the two wheels. I always pump my tires up to 120 psi in the rear, and 100 psi in the front for this reason.

A figure that is often quoted as being ideal weight distribution for a racing bicycle is 55% of the weight on the rear wheel, 45% on the front. It is one of those figures that sound about right, but has anyone ever taken the time to prove that this figure is best. I certainly didn’t in all the years I built bikes.

How would you come up with such a measurement? Maybe set a bike and rider on two sets of scales. And then the weight ratio from front to rear wheel would vary from one rider to the next because of their differing physical build.

Any vehicle or moving object will hold a straight line better if the weight is towards the front. An arrow flies straight because its weight is at the front tip, if it were at the rear it would not fly straight. In the 1960s I once owned a rear engine VW Mini-Bus. It was awful to drive in a strong wind; I would be blown all over the road.

When I first started racing in the early 1950s seat angles were around 71 degrees. We sat further back and also rode with our saddles lower than today. Gearing was a lot lower, and the theory (Back then.) was in order to pedal fast a rider had to sit back.

I always questioned this because whenever I had to make a maximum effort as in sprinting for the finish line or just to bridge a gap to a break-away, I would end up sitting on the front tip of my saddle. I would see photos of other riders sprinting and they would also be in this same forward position.

“Riding the rivet” is an expression still used today when a rider is making maximum effort. It pre-dates the 1950s when saddles were real leather and actually had rivets. Riding on the front tip where the saddle is narrower had the effect of the saddle being even lower than it already was and to my way of thinking was definitely not efficient.

It was one of the reasons I started building my own frames in the late 1950s and early 1960s. It seemed to me that when I needed to go fast, my body took up a natural position that was a lot further forward that a 71 degree seat angle would allow.

Pushing the seat angle forward actually pushed the whole frame forward making a longer wheelbase. To avoid this I made the top tube shorter and used a longer handlebar stem. This put my weight out over the front wheel and I found I had a much better handling bike. It went round corners faster and descending hills at speed felt safer.

It is often said that bike riders who are good sprinters are often good at descending hills. It is sometimes speculated that their nerves of steel that allow them to mix it up shoulder to shoulder in the chaos that is a bunch sprint, makes them fearless when descending mountains at 50 mph or more.

Maybe so, but many sprinters are big guys with a lot of weight in their upper body, chest, shoulders and arms. When in a low tuck aero position this extra weight is towards the front making bike and rider much more stable.

I have written here about “Shimmy” or speed wobble. It is a subject that gets discussed over and over on forums all over the world. It has occurred to me that these bikes with the shimmy problem are often the same well known brand of bikes that the pros use in the Grand Tours and other races throughout the season.

None of the pros experience speed wobbles, there would sure to be a video of it if they did, especially if they crashed. It has occurred to me that the fault is not with the bike, it is with the rider, and the way they have their bike set up. Or rather the way they position themselves when descending.

The pros have their bikes set with the bars set low in relation the saddle. Their weight is therefore more over the front wheel, especially when in a low tuck aero position.

If a person buys this same bike and sets it up in a more upright position because his physical limitations do not allow him to ride like a pro. They should then accept the limitations in the design of the bike which after all is designed as a racing bicycle, and if it develops a speed wobble at 45 mph. the rider should consider either a change of position or keep the speed below 45.

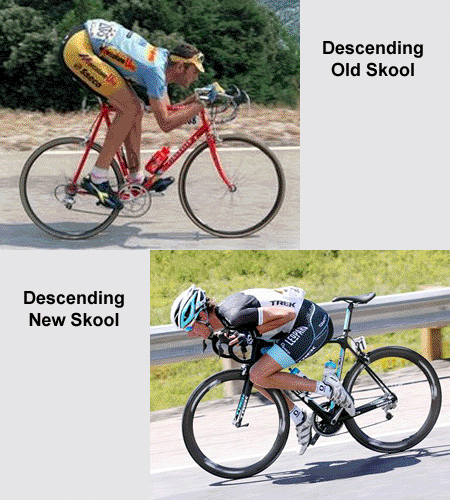

You will notice the pros descend by moving forward on the saddle, or sometimes squatting down on the top tube in front of the saddle, then rest their chest on the handlebars. This not only reduces their frontal area, but it places much of their weight over the front wheel. Therein lays a clue.

While descending you may not feel safe or comfortable going to the extreme of some of the riders in the picture above. But don’t go to the other extreme of the “Old Skool” position shown at the top. Study the picture, most of the rider’s weight is behind the bottom bracket, this is just asking for shimmy to develop.

Descending with your butt hanging off the back of the saddle is good for Mountain Bikes or Cyclo-Cross, because if you hit a bump or your front wheel drops on a hole, you could be thrown over the handlebars. However, on a smooth road at high speed this is unlikely to happen.

Move forward, lower your back and try to position most of your weight ahead of the Bottom bracket. If you achieve at least a 50/50 weight distribution you will be less likely to encounter the dreaded speed wobble.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Reader Comments (11)

Thanks for the reminder. The problem is compounded as we age and some weight gain seems inevitable as our metabolism rate slows. Need to bike more.

FWIW, That's 1984 Olympic TTT Gold Medalist Eros Poli in the top 'old school' picture, and what looks like Andy Schleck (note number ending in '1') in the New School picture.

I think if you have a bike with good geometry that fits well, has an appropriate rider position for what type of bike it is (example, NOT a race bike with a position you would use on a touring bike), you get good weight distribution as a byproduct.

Whenever the conversation turns to descending on a road bike, I always think of Marco Pantani. He was a hell of a descender and would put his hands in the drops while basically laying his chest on the saddle and hanging his butt way off the back. Hadn't put much thought into his style beyond how bad-ass he looked doing it, but I guess he could do it that way because he was so small and light it just didn't affect his weight distribution like it would have for a taller heavier rider.

That's funny, bjr, since Eros Poli is famous for winning solo the Mont Ventoux stage in the 1994 Tour, descending with impressive speed into Carpentras, a descent which saw race leader Miguel Indurain lose traction and almost crash. On the other hand, Andy Schleck is infamous for his poor descending ability, arguably because of his excessive handlebar drop which gives him a terrible position on the bike.

Jan Heine's "The Competion Bicycle" has geometry diagrams measured by the author on vintage race bikes: some selected STA values:

1894 Humber: 64 deg

1927 Alcyon Tour de France: 67.5 deg

1949 Gino Bartali: 74.5 deg

1949 Fausto Coppi Bianchi: 73 deg

1974 Eddy Merckx DeRosa: 73 deg

1981 Gitane Greg LeMond: 74 deg

1988 Landshark Andy Hampsten: 74.5 deg

So the early bikes were definitely slack, but any trend since 1949 it seems has been fairly subtle. The more obvious trend is the shortening of chainstays: Merckx rode 42.6 cm stays, which today you find only on special "Paris-Roubaix" bikes in pro racing. Hampsten's bike was down to 39.8 cm.

Anyway, fantastic blog post, as always.

At my age, if I got into that "New Skool" tuck, I wouldn't be able to get out of it. I'd go keeling over at the side of the road like Benny Hill on his tricycle.

Hi Dave,

Interesting stuff. You noted that the pro's don't experience speed wobble, and after having had a snoop looking at pro's bikes, nearly all share similarities, longer reach stems, long seatposts with a decent setback, or as small a frame as possible for the size of the rider, thus distributing their weight over a smaller frame.

As an ex-trackie I fall into the heavier upper body type, so I don't know if that is the reason I don't experience speed wobble but after years of road riding with a 53cm seat tube, 55cm top tube and 10cm stem length, I can get away with a 53 top tube, 12 cm stem along with a seatpost with a 20mm minimum setback, as long as the frame has a 74 degree seat tube angle. Same as usual dimensions just less bike, works for me on one of my race bikes, for some folks it might be worth a look to tighten things up a bit. Descending I do what you suggest nothing radical, just wish I could get some speed wobble on my fixed wheel.

That's funny, bjr, since Eros Poli is famous for winning solo the Mont Ventoux stage in the 1994 Tour, descending with impressive speed into Carpentras, a descent which saw race leader Miguel Indurain lose traction and almost crash. On the other hand, Andy Schleck is infamous for his poor descending ability, arguably because of his excessive handlebar drop which gives him a terrible position on the bike.

Jan Heine's "The Competion Bicycle" has geometry diagrams measured by the author on vintage race bikes: some selected STA values:

1894 Humber: 64 deg

1927 Alcyon Tour de France: 67.5 deg

1949 Gino Bartali: 74.5 deg

1949 Fausto Coppi Bianchi: 73 deg

1974 Eddy Merckx DeRosa: 73 deg

1981 Gitane Greg LeMond: 74 deg

1988 Landshark Andy Hampsten: 74.5 deg

So the early bikes were definitely slack, but any trend since 1949 seems has been fairly subtle. The more obvious trend is the shortening of chainstays: Merckx rode 42.6 cm stays, which today you find only on special "Paris-Roubaix" bikes in pro racing. Hampsten's bike was down to 39.8 cm.

Anyway, fantastic blog post, as always.

Interesting that to balance better on the bike, most say move your saddle behind the BB more. That un-weights the upper body, and makes the ride more comfy. BUT, to get a more stable riding bike, you should be more forward with more weight over the front wheel.

A catch 22?

Thanks Dave, I always learn something from your posts!

When I wobble though, it's usually because I'm just too slow. Don't think shifting to a fully tucked position would help, but my dog told me assuming an aero position on my commuter as I roll to a stop light would look cool. I think he just wants to take a video he can post to make fun of me.

Hi Dave,

I had a neighbor who worked as a motorcycle tester for Kawasaki. He often acted as an expert witness at court hearings where someone (usually a police officer) was hurt as a result of speed wobble. He showed me a video of him riding very fast, taking his hands off the bars and inducing a speed wobble by striking one end of the bars with the heel of his hand. The video then shows him stopping the wobble by simply leaning forward: still no hands. As a point of reference, when I knew him he was in his 70s. The cops usually had broken arms from trying to strong-arm the bike to stop the wobble.

-Rob

I thought I had read about Jan Heine (Bicycle Quarterly) testing weight ratios but when I looked it up, he was testing pressure and tire drop. His charts assume the 45/55 ratio. The link is here:

http://janheine.wordpress.com/2010/10/18/science-and-bicycles-1-tires-and-pressure/

More fascinating data to fit with Dave's interesting post.

Cheers, Gene in Tacoma