Fausto Coppi: Il Campionissimo

Thu, January 24, 2008

Thu, January 24, 2008

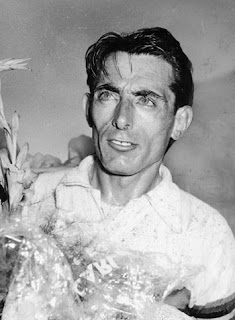

Italian cyclist Fausto Coppi was one of the most successful and popular cyclists of all time.

Like Gino Bartali his career was interrupted by WWII; however, the big difference was, he was five years younger than Bartali; Coppi was 25 when war ended, Bartali was already past 30.

His pre-war successes came early, he won his first Giro d’Italia in 1940 at age 20; to this day the youngest ever to do so.

During the war in 1942 he set the world hour record (Unpaced.) at the Vigorelli Velodrome, in Milan.  He covered 45.798 kilometers (28.457 miles.) in one hour. (Picture left.) A record that would stand for 14 years until broken by Jacques Anquetil in 1956.

He covered 45.798 kilometers (28.457 miles.) in one hour. (Picture left.) A record that would stand for 14 years until broken by Jacques Anquetil in 1956.

One year after setting this record Fausto Coppi was in the Italian army, captured by the British, and held as a prisoner of war in North Africa; where he remained until the war ended.

Coppi’s post war career in the late 1940s and early 1950s is the stuff of legends. When on form he was unbeatable, many times simply riding away from the opposition to finish solo often minutes ahead.

For example in the 1946 Milan-San Remo race; Coppi attacked with nine other riders just 3 miles (5 km) into the 181 mile (292 km) race. On the climb up the Turchino, Coppi dropped the nine riders and went on to win by 14 minutes over the second placed rider, and by 18:30 over the rest of the peloton. Anyone who has raced knows how difficult it is for a solo rider to stay ahead of a group of riders working together. To take 14 minutes out of such a group is phenomenal.

Anyone who has raced knows how difficult it is for a solo rider to stay ahead of a group of riders working together. To take 14 minutes out of such a group is phenomenal.

Fausto Coppi won the Giro d’Italia five times; a record he shares with Alfredo Binda, and Eddy Merckx. He won the Tour de France twice in 1949 and in 1952, both times, dominating the competition and winning both the mountains jersey and the overall race.

Coppi was 1.87 meters (6’ 1 ½”) tall, and weighed 76 kg. (167 lbs.) obviously a great athlete with a huge rib cage that no doubt housed a large heart and lungs. However, he was fragile physically with brittle bones, brought on by malnutrition as a child.

He suffered no fewer than twenty major bone fractures from falls while either racing or training. At different times, he broke his collarbone, pelvis, and femur, as well as displacing a vertebra. He also had a sensitive immune system and suffered several serious illnesses over the years. As a result, there were sometimes large gaps in his career when he was either injured or sick.

He also had a sensitive immune system and suffered several serious illnesses over the years. As a result, there were sometimes large gaps in his career when he was either injured or sick.

Fausto Coppi also suffered a personal tragedy in 1951 when his brother Serse Coppi died from a head injury after he fell in the finishing sprint of a race. This happened just five days before Fausto was to ride the Tour de France. Deep in mourning with his mind not on racing, he finished in tenth place.

There is speculation even to this day that had it not been for the war, the injuries and the other setbacks over the years, Fausto Coppi’s career may have equaled or even surpassed that of Eddy Merckx.

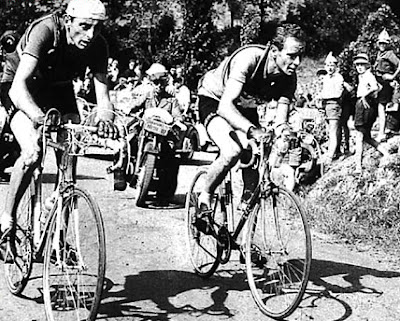

He was around at a time when there were so many other great riders. Bartali, Kubler, Koblet, Bobet, Robic, Geminiami, to name but a few. On his day Fausto Coppi was head and shoulders above all of them. Above: Fausto Coppi with Ferdi Kubler leading by a nose.

Above: Fausto Coppi with Ferdi Kubler leading by a nose.  With Hugo Koblet.

With Hugo Koblet. With the diminutive Frenchman Jean Robic on his wheel.

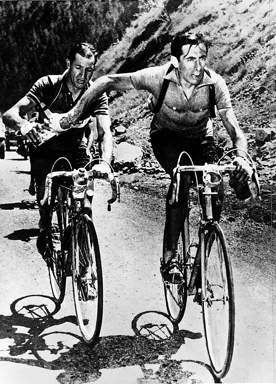

With the diminutive Frenchman Jean Robic on his wheel. Sometimes rivals, Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi share a drink.

Sometimes rivals, Gino Bartali and Fausto Coppi share a drink.

Made out to be arch rivals, Bartali and Coppi in real life were probably friendly rivals. Bartali was certainly instrumental in helping the young Fausto early in his career. Taking him on as a domestique in his team, and when Bartali crashed in the 1940 Giro and lost hope of winning, he assisted the young Coppi to his victory.

One has to understand the mood of the Italian people at that time. Coming out of a terrible war and a long dictatorship, the nation was crushed both physically and morally. They looked for redemption, and found it in their cycling heroes. Bartali and Coppi were unofficial ambassadors for their country. There were two factions that the Italian press played on; Fausto and Gino became symbols of divisions within the country. Two opposite, and sometimes irreconcilable points of view.

There were two factions that the Italian press played on; Fausto and Gino became symbols of divisions within the country. Two opposite, and sometimes irreconcilable points of view.

The push for modernization and new thinking on the one hand, and the importance of traditions, mainly linked to the Catholic religion on the other. So it became “Gino the pious” verses “Fausto the sinner,” at least in public opinion. Italy’s sports divisions in the 1950s reflected the country's social ones.

Further strengthening pubic opinion were some facts of Coppi’s private life. Right after he won the World Road Championship in 1953, Fausto, a married man, was seen with another woman. Giulia Occhini, known in the press as La Dama Bianca. (The Lady in White.)  In late 1959, Coppi went on a hunting trip in North Western Africa, where he contracted malaria. He became ill on returning to Italy; the disease was treatable even at that time, but was miss-diagnosed by doctors. Fausto Coppi died on January 2nd, 1960; he was 40 years old.

In late 1959, Coppi went on a hunting trip in North Western Africa, where he contracted malaria. He became ill on returning to Italy; the disease was treatable even at that time, but was miss-diagnosed by doctors. Fausto Coppi died on January 2nd, 1960; he was 40 years old.

So came a tragic end to the life of a great cyclist, one of the best there has ever been. Today in Italy Fausto Coppi is mostly remembered as Il Campionissimo or “The Champion of Champions.”

Pictures from: .Progetto Ciclismo

To view more great pictures (Including some shown here.) go to www.FaustoCoppi.it Click on "Cartoline," chose number of pics per page (9, 15, 30, 60.) Click on "Guarda" to enlarge.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Reader Comments (16)

A thing you missed out was how its said that after the war, quite a few roads were built wherever Coppi rode his bike.

"Anyone who has raced knows how difficult it is for a solo rider to stay ahead of a group of riders working together. To take 14 minutes out of such a group is phenomenal....."

As for the above comment, yes, Coppi was a legend but before making an idol out of him, we have to remember he himself admitted several times that "you dont win a bike race on mineral water alone"

Interpretations are open but doping was quite rampant.

To read the rich cycling culture from the pages of history is great but its not possible to look up to these people anymore, atleast for me.

May I add something small.

For riders today: If you cycle the Col d'Izoard , there is a terrific monument near the top on the South side. About one kilometre from the top and half way between the famous Casse Desserte and the summit.

See the second photo in the link. It is a plaque to Bobet and Coppi.

Bobet and Coppi monument

In the case of these greats from an earlier time, it always fascinates me to wonder what might have been if such brilliant careers weren't interrupted by war.

Wonderful post.

This may be a stretch but would you have anything for cyclists with clavicle fractures.

July 27 2007 I was hit from behind by an unknown vehicle. Above and beyond a prejudiced police investigation (the officer refused that of my input that did not agree with that of his report at the time) I've been diagnosed with a non-union.

In layman's parlance non-union means the bone segments will not heal together. I NEED to get back on the bike. Are you aware of any device/method cyclists have used in the past to get back in the saddle?

Medical advice is beyond my scope of expertise. However, I do know that exercising your good leg will benefit your other leg. (I’m assuming only one leg was injured.) Maybe some weight training in a gym on your good leg.

I broke my right arm in 1970 and it was in a cast for five months. I rode a fixed gear bike steering with my left hand only; read the account of my experiences in my blog here.

When my doctor took the cast off he was amazed to see I still had muscle in right arm. By exercising my left arm and the rest of my body it had helped the disabled arm.

However, I urge you to seek out expert advice, preferably from a sports doctor. I wish you well in your recovery. You seem to be determined to get back on a bike again and a positive attitude will always win out in the end. Take it slow and easy, you will get there in time.

Dave.

Sorry, I should have been more clear. It is the collar bone that is broken. My understanding is 1% of collar bone fractures result in non-unions and evidently I'm one of the unlucky few. I'd just hoped in your travels you might have learned of other cyclists who have found means to remount with a clavicle fracture. I'm considering obtaining a figure of eight brace but wonder if this has been tried and if there are any warnings that go with this exercise. As for the advice of my doctor(s) in the matter it is all rather obscure and imprecise. My last orthopedic surgeon seemed of the impression if I could tolerate the pain it would be ok. I have gleaned warnings from the web that mostly discourage those healing from trying this due to the probability of refracture but that would not be applicable to me due to this being a non-union. As reaching forward seems the most uncomfortable I'm of the consideration that wearing a brace that holds the shoulder back (as would a figure of eight brace) wearing one may just be my ticket to ride. Are you aware of any who have tried similar?

I too suffered a non-union clavicle fracture. I had surgery to repair it. Seven screws and a plate, and aside from abit of numbness at the area of incision, I'm back to both road and mountain biking with no problems.

I have been at the Pordoi pass in the italian dolomites where there is one of the monument in memory of Fausto Coppi.

http://picasaweb.google.com/martino.usa/Sellaronda

The translation of the memorial tablet is:

"Under the shadow of this magnificent dolomites peaks this bronze monument will remember forever the incomparable exploits of the greatest cyclist: to Fausto Coppi, il Campionissimo"

Thanks Dave to remember this great champion...

Martino

Oh! This is awesome! Thanks for dispelling a few

misunderstandings I had read regarding this lately.

Great Job: however, there is one error: Fausto Coppi was only 1.77 meter, not 1.87 as mentionned. If you see Coppi standing next to Gino (1.71m), or next to Louison Bobet (1.78m). you can see that he could not have been 1.87! Furtheremore, Hugo Koblet who was 1.82m, is taller than Coppi when they stand next to each other.

Heard that Coppi would just break other cyclists wills. On uphills he just seemingly tirelessly picked up more speed as the other cyclists crumbled below him. One might judge him one of sports greatest aerobic and (pain) endurance phenomenons. Not only a great champion, but a super sportsman.