Finally, a mini-pump that actually works.

Tue, November 17, 2015

Tue, November 17, 2015  Bicycle tires, especially clincher tires, have greatly improved in the last twenty years or so. Back in the 1980s if you wanted a high performance tire for your high performance bike, you had to go with tubular tires, or sew-ups as they are called in the US. For the non-racing leisure rider this was a huge hassle and expense.

Bicycle tires, especially clincher tires, have greatly improved in the last twenty years or so. Back in the 1980s if you wanted a high performance tire for your high performance bike, you had to go with tubular tires, or sew-ups as they are called in the US. For the non-racing leisure rider this was a huge hassle and expense.

Today there is a wide range of performance clinchers to choose from, but a simple portable air pump to carry on the road, along with a spare inner tube and/or a patch kit. One that will put enough air in the tire to get you home in an emergency. Not so easy to find.

Most real bike enthusiasts have a floor pump (Track Pump.) to air up their tires at home.

Most real bike enthusiasts have a floor pump (Track Pump.) to air up their tires at home.

But the full length frame fit pump, the kind one could use to beat off an attacking dog, disappeared when lugged steel frames disappeared.

Such a pump would pump up your tires, in fact in the old days it was all we had, and our pressure gauge was our thumb and forefinger.

The mini-pump has taken over from the full length pump, but if it won’t pump your tires up when needed, what use is it?

I have been struggling with such a mini-pump for at least two or three years. Like most of its kind it has a push-on air chuck that can be adapted (By reversing a rubber washer.) to fit either a Schrader or the smaller Presta road tire valve.

My first emergency road side flat, the pump was letting air out of the tire as fast as I was pumping it up.

My first emergency road side flat, the pump was letting air out of the tire as fast as I was pumping it up.

Then I found I had bent the valve pin in the Presta valve. In trying to straighten it, it broke off and I had to start over with a second spare inner tube.

I then bent the second valve pin, but did not attempt to straighten it and got enough air in the tire to get me home.

After that I realized this pump was only good for putting a little air in the tube so it didn’t get pinched when fitting the clincher tire over the rim. I used a CO2 pump to bring the tire up to full pressure.

So when I was recently offered the “Road Air” mini-pump to try out, I was pleased to see it had a simple, ‘old tech’ screw on flexible connector. The kind of connector pumps had from day one when the pneumatic tire was invented in 1887, and worked fine for the next 100 years. (Picture below.)

The built in push-on connector has been around since at least the 1930s and also worked fine with the full length pump. It was born out of necessity like the quick release hub because of racing. Even the professional riders had to change their own tubular tire, and pump it up, in races like the Tour de France. Picture below, Romain Maes pumping up a tire with a push on air chuck, in the 1936 TDF.

This “Deal with your own punctures,” regulation was still in place in professional racing throughout the 1950s. It was done in the interest of fairness because not all teams had a full support vehicle. In amateur races it went on into the 1980s, in all but the top races.

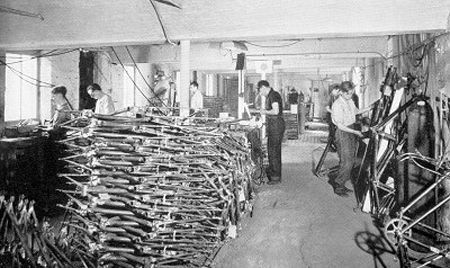

By the 1980s the Silca, frame fit pump was popular. It came in various lengths so you could buy one to fit your frame. Back in the day I painted many Silca pumps to match the frame. (Below.)

So a pump is no longer needed for racing, and the urgency to get a tire pumped up quickly is not the problem. The issue is, get the tire pumped up and get home. The built in push on air chuck is no longer needed on a mini-pump, and they don’t work anyway.

The reason. With a full length pump, one is pumping with long slower strokes. Because of the leverage it was easy to keep the air chuck firmly on the valve with one hand, while pumping with the other. Because a mini-pump is only 8 or 9 inches long, it is necessary to pump in fast short (Almost frantic.) strokes, and it is almost impossible to hold the air chuck steady, hence my experience with bent valve pins.

The flexible rubber connector on the “Road Air” pump is under a neat little plastic dust cap. Lift the dustcap and the connector unscrews from pump to extend it, but remains attached to the pump. It fits a Schrader type valve, and you have to use the Presta adaptor (Provided.) for a road bike.

(Above.) The handle opens up, and contains a Presta adaptor, a needle connector for blowing up soccer balls, and a plastic nozzle for blowing up anything else that needs air. The compartment in the handle is quite hard to open and my first attempt it came off suddenly and the contents went flying. Had I been at the roadside the Presta adaptor would have been lost in the long grass with all the other parts.

(Above.) The handle opens up, and contains a Presta adaptor, a needle connector for blowing up soccer balls, and a plastic nozzle for blowing up anything else that needs air. The compartment in the handle is quite hard to open and my first attempt it came off suddenly and the contents went flying. Had I been at the roadside the Presta adaptor would have been lost in the long grass with all the other parts.

I found it best to lever open the handle with a small pen knife I always carry on my key ring. (Left.)

I found it best to lever open the handle with a small pen knife I always carry on my key ring. (Left.)

I always have a spare Presta adaptor in my patch kit anyway, so I’m covered.

I would prefer a Presta valve only version, and I don't need all the other stuff.

The maker would save money on a plain handle instead of one that opens.

There are enough road bike enthusiasts out there, I would expect there to be a good market.

When this little pump arrived, I let all the air out of one of my tires and connected it up.

When this little pump arrived, I let all the air out of one of my tires and connected it up.

Two minutes of fast pumping and my thumb and forefinger told me there was enough pressure in the tire to get me home if I was on the road.

The pump comes with a little carrying bracket that fits on a water bottle mount. I prefer to carry it in my pocket.

The two minutes it took me to pump up my tire, was the time it took to sell me on this pump. It pumped my tire up, that’s all I ask. This is a great little pump.

Buy the Road Air Pump here. Reasonably priced at $24.95 and comes with a lifetime guarantee.

To Share click "Share Article" below

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |