Joining metal by brazing became the method of choice when the bicycle was invented in the late 1800s. Early bicycle lugs were in fact pipe fittings, but greater strength was needed, so brass was used instead of lead base solder.

Soldering and brazing are pretty much the same process, flux is required to allow the solder or brazing material to flow. The difference is the melting temperature of the different materials.

Soldering takes place at 427 degrees centigrade and below. Brazing between 593 and 895 degrees centigrade. Different sources will give a slightly different range, but as silver and brass will both melt within the range for brazing, that is the correct term. Brass brazing or silver brazing,

Silver is often known as Silver Solder, but strictly speaking it is not soldering because the melting temperature is above 427 degrees. Silver brazing rods come in soft, medium and hard, the soft being at the low end of the temperature range, progressing to a higher melting point for the medium and hard.

Silver is more expensive as it is for the most part silver, alloyed with other materials such as cadmium, or nickel. The price of silver brazing rods, will fluctuate with the price of silver on the Precious Metals Market.

Brass is already an alloy of copper and zinc, other materials will be added to give desired characteristics, like flow properties and workability. Brass melts at the higher end of the brazing range.

Often silver brazing is quoted as being best for lightweight bicycle frames because it melts at lower temperature. However, in the hands of a novice it is just as easy to overheat a joint using either silver or brass. In fact if you overheat a joint using silver, the silver will no longer flow, and the joint will have to be torn apart, thoroughly cleaned and start all over again.

Most framebuilders become proficient in either silver or brass, but my guess is, only a few totally master both. I became proficient with brass, but never built a complete frame using silver. The only time I used silver, was for brazing water bottle bosses, and top tube cable guides. The reason: Using the higher temperature brass would put a slight ripple in the thin un-butted part of the tube that would show after painting.

The traditional front and rear drop-outs, (Campagnolo for example. (picture left.)

The traditional front and rear drop-outs, (Campagnolo for example. (picture left.)

The type where the front fork blade, chainstay and seatstay are slotted to take the drop out, have to be brass brazed.

Silver will not fill in the gaps, or fill the hole in the end of the tube. So even a builder who uses silver for the main frame will use brass for this type of drop-out.

Silver requires closer tolerances for example where the tubes fit in the lug. My method of altering the angle of the lug with a small hammer as I brazed, could not have been done with silver. The steel lug had to be at a bright red heat in order to be malleable enough to reshape. This would be too hot for silver.

Brass historically has always been used in Europe, which of course includes the UK where I learned to braze using brass. As a framebuilder becomes proficient at brass brazing, he learns to braze a joint cleanly, and not spill globs of brass over the edges of the lug. If this happens the builder will spend hour’s hand filing the excess brass away. Possibly leaving behind ugly file marks.

Silver on the other hand is softer and the excess can be sand-blasted away, or even scraped away with a small penknife. The fine and intricate, sharp edge lug work carried out by the late Brian Baylis, could not have been achieved using brass. English builder Hetchins did some fine elaborate brass brazed lug work, but on close inspection the corners and edges are not as fine and sharp as one can achieve with silver. (Baylis below left. Hetchins below right.)

Silver brazing bicycle frames on the scale it is used today is an American development that can be traced all the way back to the Schwinn Paramount. Read the history here. One of the reasons the Schwinn Paramount was built using silver, was the easy clean up.

The intricate Nervex lugs used (Right.) would have been a pain to brass braze cleanly.

The intricate Nervex lugs used (Right.) would have been a pain to brass braze cleanly.

Many of the early American builders were influenced by the Schwinn Paramount, and a few even apprenticed there.

Brass or Silver? Both have their own advantages and disadvantages. Both require different skill-sets.

I could never have done what Brian Baylis did, and on the other hand, he could not have built the number of frames I built using the methods he did.

Brass is more suited to production, silver is more suited to the artisan builder, custom building frames one at a time.

In my opinion, brass in many ways is more forgiving from a workability standpoint. For an absolute beginner, don’t be misled into thinking silver is easier.

Try brass brazing a few pieces of scrap metal together. You will have a lot of fun for not too much money. And a lot less heartache, than spending a ton of money by plunging straight in, and trying to silver braze a frame with little or no experience.

To Share click "Share Article" below.

To Share click "Share Article" below.

Mon, October 31, 2022

Mon, October 31, 2022  I was recently contacted by Joe Cirone, (Left.) who lives in Visalia, CA. Joe is now 92 years old and raced bikes, with success back in the late 1940s early 1950s.

I was recently contacted by Joe Cirone, (Left.) who lives in Visalia, CA. Joe is now 92 years old and raced bikes, with success back in the late 1940s early 1950s. Joe Cirone leads in a 1000 m. Match Sprint. 1948 US Nat. Championship.Joe tried out for the Olympic Team in 1948 but fell short by a little over one second in the 1000 meter Time Trial, held in Milwaukee Wisconsin. He did however take 2nd in the Nationals Senior Championship that year held in Kenosha Wisc.

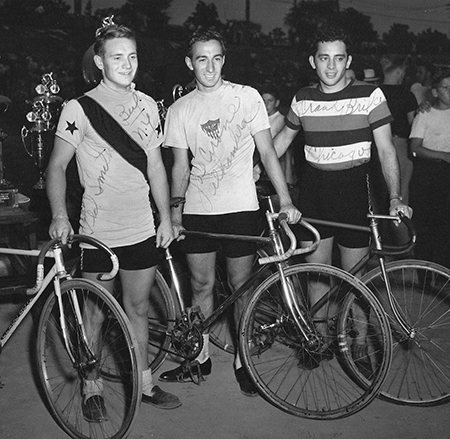

Joe Cirone leads in a 1000 m. Match Sprint. 1948 US Nat. Championship.Joe tried out for the Olympic Team in 1948 but fell short by a little over one second in the 1000 meter Time Trial, held in Milwaukee Wisconsin. He did however take 2nd in the Nationals Senior Championship that year held in Kenosha Wisc. 1948 US Nat. Championships. Joe Cirone center.In 1951 Joe was part of a "Special American Team" that went to Japan on a "Good Will" Tour for one month. He raced against Japanese Teams up and down Japan. The team averaged two races each week, ending in a Special Event in Tokyo Stadium.

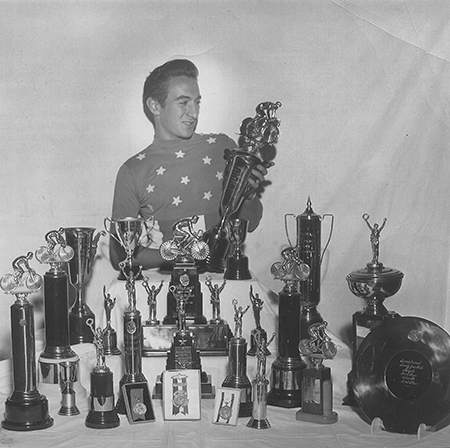

1948 US Nat. Championships. Joe Cirone center.In 1951 Joe was part of a "Special American Team" that went to Japan on a "Good Will" Tour for one month. He raced against Japanese Teams up and down Japan. The team averaged two races each week, ending in a Special Event in Tokyo Stadium. Joe Cirone with his collection of Trophies.Some links to previous articles:

Joe Cirone with his collection of Trophies.Some links to previous articles:

Art and Function

So is a bicycle art or just something you ride? Well, yes and no. There is pure art, objects that serve no practical purpose other than to be pleasing to the eye. To live a life without art would be a pretty bland existence.

I am not a material person by any means. I do not place much importance on stuff, but I do have pictures on my walls, and a few pieces of handmade pottery around. They bring me pleasure, and my life and my home would be missing something if they weren’t there. That is the only purpose of these art objects.

Because given a choice between two objects of equal performance and price, one will choose the one more pleasing to look at.

Furniture is a good example of functional art. A chair has to be comfortable to sit in, but also needs to be pleasing to look at, because it becomes part of the décor of our homes, along with the pictures on the wall.

There are degrees of function and art in functional art, and when one takes over from the other the product often suffers one way or another. But it all comes down to what the consumer or owner of the object wants, and what he can afford or is willing to pay.

If it brings pleasure to its owner just to look at it, that is its purpose. I would not criticize anyone for owning such a chair, or the person who made it.

So is a bicycle frame any different? I got into building frames to build a better bicycle. One that rode better, handled better, and was more comfortable. My customers in the UK were almost 100% racing cyclists. The bike was needed to compete in bike races, it sold because it was functional and the price was right.

When I came to the US I had to up the ante on my finish work because that is what the American consumer demanded. The bikes did not lose any of the ride or handling qualities, but I did reach a point where people began to say, “This is too beautiful to race, I will be afraid to crash it.”

This annoyed the hell out of me. I had been forced to move towards pure art in order to stay competitive, then the bike was no longer practical as a racing bike, because it was too fine and too expensive.

That is why I moved away from the pure custom frame to the limited production model like the Fuso. A Fuso will handle exactly the same as one of my super expensive customs, but the price was reasonable, and the degree of finish was acceptable to the people who wanted a piece of art.

On Steve’s point that the framebuilder only makes the frame, not the complete bike. It has always been that way. Even today, companies like Trek and Cannondale, design and produce a frame only, then assemble it with the same components as everyone else. And the bicycle always takes on the name of the frame builder or manufacturer. It becomes a Trek bicycle, or a Dave Moulton, a Fuso or a Brian Baylis bicycle.

Even lower end bicycles are built this way. The only exception I know to this was Raleigh Industries, in Nottingham, England. They had a huge factory that made everything. They had different thread standards, and even different rim and tire sizes, so if you bought a Raleigh bike, you were forced to buy spare parts and even tires from Raleigh. They went out of business some years ago, and I don’t know of anyone manufacturing the whole bike anymore.

To sum up, I believe there is room for art and room for function, and when you can successfully combine the two you have the best of both worlds. I never spent as much time building a bicycle frame as Brian Baylis, but I did spend a year and a half writing a novel. Was that a waste of time? You tell me, because I often wonder about that myself.