The 1st Tour of Britain: 1951

Mon, September 26, 2011

Mon, September 26, 2011

"VIDEO 1951 TOUR OF BRITAIN"

In 1951 I was 15 years old and had my first lightweight bike; I would have to wait another year until I could race at 16 years old.

It was also the year the first Tour of Britain was held; I remember riding with a school friend, 40 miles to watch the final stage as they passed through Baldock, Hertfordshire on the A1, on their way to London.

The event was run by the “British League of Racing Cyclists,” (BLRC) a “Rebel” organization that had broken from the National Cyclists Union (NCU) in the 1940s when they organized a race on open roads from Llangollen in Wales to Wolverhampton in the West Midlands of England.

The 1940s was of course during WWII and there was very little motor traffic on the roads; in spite of this the NCU refused to sanction the race, and a group of riders lead by Percy Stallard from Wolverhampton ran the race anyway.

The NCU, recognized at the time by the UCI as the official governing body of cycle sport in the UK, had upheld a ban on mass start cycle racing on the open road since the late 1800s. By the 1950s the BLRC had proved that massed start races could be held on the open roads, safely and with full cooperation from the police.

The first Tour of Britain was sponsored by the “Daily Express” a major national newspaper. As these old British Pathe Newsreel clips show there were huge crowds of spectators out to watch the race. It shows hundreds of club riders following the race on bikes as the riders leave London.

Also these Pathe Newsreels of the race were shown in theatres throughout Britain, creating more interest from the general public. The TOB was a huge success and has been held every year since 1951. It became known as the Milk Race for a number of years when the Milk Marketing Board took over sponsorship from the Express.

"TOUR OF BRITAIN" - HALFWAY

The race brought about credibility and acceptance for the BLRC; eventually the BLRC and the NCU would reach agreement and amalgamate in 1959 to become the British Cycling Federation. (BCF) I wrote a three part series on the History of British Cycle Racing.

In the first TOB the roads were not closed and the riders had to deal with normal traffic as they raced; although at that time not anywhere near as heavy as today’s traffic.

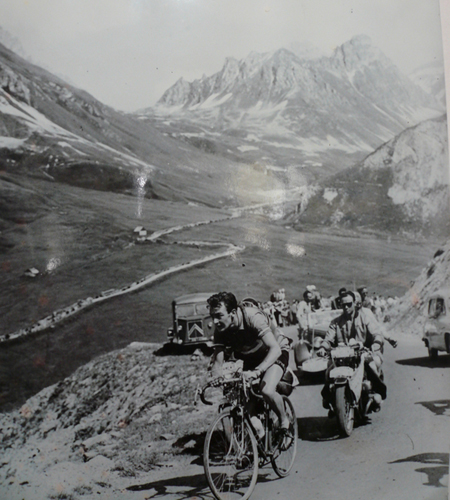

In the first video there is a shot of Dave Bedwell sprinting to win the second stage with cars coming in the oposite direction. Dave Bedwell would later be part of a British team to ride in the 1956 Tour de France. Pictured below (Left.) riding along side none other than Fausto Coppi.

The second video shows Scottish rider Ian Steel who was the eventual overall winner of the 1st. TOB; it also mentions Derrick Buttle in a break away over “The Shap” one of the bigger climbs. I recently read that Derrick Buttle is still riding to this day, now aged 81.

One thing always stands out when I see these old clips from the 1950s and before; the high cadence these riders pedal at. 14 teeth was the smallest sprocket you could get back then, the largest standard chainring was 51 teeth. The highest gears were reserved for downhill or sprinting; on the flat sections they would be riding 51 x 16. (86 inches.)

People riding road races in the UK today can thank these early rebel pioneers, without them there would be no Mark Cavendish or Bradley Wiggins competing in the Tour de France. Time Trials on flat courses are not condusive to developing world class riders and that is where the UK would be stuck if it were not for the BLRC, “The League” as it was affectionally known

TOWN OF CYCLES

This final clip has nothing to do with racing but shows Oxford in 1950. Note that no one locks their bike; they just park it and leave it and the bike is there when they return. But few people locked cars either back then; these were simpler times.

My thanks to regular reader Mark Frank who turned me on to the Pathe News website. The videos do not play live here, but click on the pictures and they link to the Pathe News site. If you type in "Cycling" in a search you will find other old clips from the Tour de France, Giro d'Italia, the Classics, Cyclo-cross, etc., some dating back to the 1930s. All great stuff.

Gears: On Reflection

When I posted the first article on gearing a week ago, it was not my intention to extend it into a series. However, it is a subject that has caused me to reflect on how things were, and to speculate how we arrived at where we are today.

Going back to the turn of the last century, because Britain was initially the center of the bicycle industry, the bicycle chain was quickly established at half an inch pitch. It has remained the standard worldwide ever since, even in countries where the metric system has always been in place.

Although chains are made in all manner of pitches for industrial use, ½ inch pitch has always worked fine on bicycles, and there is little reason to change it. I seem to remember Shimano introduced a one centimeter pitch chain for track bikes back in the 1980s, but it was short lived.

Sprocket and chain width was set at one eighth of an inch, and remained so for 50 or 60 years. The introduction of the five-speed freewheel made it necessary to make the sprockets narrower, and the 3/32 inch wide chain came into being.

The six-speed freewheel was introduced (I believe.) in the early 1970s, and was achieved by widening the spacing between the frame’s rear dropouts, from 120mm. to 126mm.

This remained the standard set up until about the time I left the bike business in 1993. I know this because all the frames I built in the US had 126mm. rear spacing.

Soon after gears quickly went from 6 to 7, 8, 9, and 10 speeds; and with it 130mm. rear spacing; all within a relatively short span of years, considering how long the 5 and 6 speed was the standard.

I remember when Shimano first introduced index or click-shifting in the late 1980s, I was one who scoffed at it, along with most Europeans.

I remember talking to people from Campagnolo and they likened the idea to “Putting frets on a fiddle.” A violin has no markings where to place your fingers to play a given note; throughout history people learn by experience where to place their fingers.

It was the same with shifting gear on a derailleur. People like me who grew up using friction shift gears could not understand why anyone would want to complicate something so simple.

Of course the mountain bike was a whole different story, down tube shifters were not practical, and it lent itself to a ratchet type, handlebar gear control. Also, here was a whole new generation of users not raised on the traditions of road bike use.

Throughout history, the design of the racing bicycle, and its components, was always dictated by what the European professional riders used. The MTB was an American phenomenon and the rules changed.

I remember Campagnolo lost a huge share of the component market in the US to Shimano, because they were slow to get into index shifting, and spent several years playing catch up.

Click shifting made it possible to go up to 10 speeds. Although it may have been possible with friction shift; never-the-less it would not have been practical.

One commenter asked if riders were stronger in the old days; I don’t think so, we just made do with what we had.

The Tour de France was run on single gear bikes up until the late 1930s, and the riders went over the same mountains they do today; plus the roads were often no better than dirt tracks.

Our top gears were in the 90s, but we trained on very low gears and so learned to pedal fast. At the other end, I never had a gear that was lower than 50 inches, and never found a hill I couldn’t climb on it.

I was always taught that in terms of energy spent it was better to climb a hill on the highest gear possible. I don’t know how that jibes with today’s thinking, but when 50 inches was your lowest gear you had no choice but to stay on top of it and keep the revs at a reasonable level, or you were finished.

With today’s gears in the 30s and 40s, it is only natural that you are going to use them, and spinning a low gear on a steep gradient is exhausting.

I am not talking of a slow walking pace, but one of racing speeds. It takes a special rider of great stamina to do that

Footnote:

Top picture is my current set up. I was lucky enough to find a 48 chainring on eBay; it was actually an inner ring, but works fine as an outer. The inner ring is a 39. With a 14 to 19 straight up six-speed freewheel it gives me gears from 92 to 55 inches. Pretty close to the range I had in the 1950s