Jean Robic: The little giant

Tue, July 10, 2007

Tue, July 10, 2007  Very tall men always stand out in a crowd, but then so too do very small men who reach greatness.

Very tall men always stand out in a crowd, but then so too do very small men who reach greatness.

French rider Jean Robic was such a man; barely five foot tall one would have expected he would have been more suited to a career as a jockey, rather than a world class cyclist.

His small stature and obvious physical strength made him a formidable climber. On the decents his light weight was a definite disadvantage and he made up for this by taking chances and pushing his speed to the limit

He crashed often and it was probably because of this he always wore a padded leather helmet. Only track riders wore helmets back in those days, so it was unusual to see a professional road rider use one as a matter of course. This earned him the nick name of "Leather Head." Robic won the 1947 Tour de France. This was the first Tour after WWII and his win was no doubt a huge morale booster for the French people. If Jean Robic was an unusual rider his win of the 1947 tour was no less unusual; he did so by winning on the very last stage without ever wearing the Yellow Jersey throughout the race.

Robic won the 1947 Tour de France. This was the first Tour after WWII and his win was no doubt a huge morale booster for the French people. If Jean Robic was an unusual rider his win of the 1947 tour was no less unusual; he did so by winning on the very last stage without ever wearing the Yellow Jersey throughout the race.

Robic was not even in the running until the 15th mountain stage (Luchon - Pau ) when he took off on his own to win by 10 minutes over the second placed rider.

Early on the last stage Robic sprinted up a short climb to take a prime; or so he thought. He was not aware that there was a small break-away group ahead of him, and had he known he never would have sprinted.

This was not unusual back in 1947, there was little or no communication between riders and team support, in fact team support was minimal in those days. A rider could be in the middle of the peloton, and not know that a break had occurred. Robic was joined by two other riders and because they thought they were leading, worked together, and rode hard, but when a rider dropped back from the leading group. They never caught the leading group, but because they had ridden hard all day chasing the leaders they took 13 minutes out of the peloton that included Pierre Brambilla in the Yellow Jersey who had remained back in the peloton. Jean Robic had won the Tour with the shortest overall time; Brambilla was relegated to third place.

Robic was joined by two other riders and because they thought they were leading, worked together, and rode hard, but when a rider dropped back from the leading group. They never caught the leading group, but because they had ridden hard all day chasing the leaders they took 13 minutes out of the peloton that included Pierre Brambilla in the Yellow Jersey who had remained back in the peloton. Jean Robic had won the Tour with the shortest overall time; Brambilla was relegated to third place.

Throughout the rest of the 1940s and into the 1950s Jean Robic held his own among other great riders of that time like Coppi, Kubler, Bobet, etc. In 1950 Robic won the first World Cyclo-cross Championship. (Left.)

Throughout the rest of the 1940s and into the 1950s Jean Robic held his own among other great riders of that time like Coppi, Kubler, Bobet, etc. In 1950 Robic won the first World Cyclo-cross Championship. (Left.)

He was one of my heroes when I started riding in the early 1950s. One of the most photographed riders of that era, I remember seeing so many close up shots of Robic, his face showing all the extreme pain and agony of the sport.

Other shots of him bleeding profusely from cuts to his face, elbows and knees after falling. He was depicted in cartoons riding heavily bandaged and with his arm in a sling.

I was a little surprised to find very few photos on the Internet, even on French sites. I am grateful to The Wool Jersey for the few great pictures I did find

The picture above shows Robic dealing with a flat tire in the 1948 Tour. As I said earlier team support was minimal and all riders carried a spare tubular, usually around their shoulders.

The picture above shows Robic dealing with a flat tire in the 1948 Tour. As I said earlier team support was minimal and all riders carried a spare tubular, usually around their shoulders.

In the picture Robic has changed the tire, the punctured tubular lies in the road under his feet, as he struggles to replace the chain. Note the pump carried on his down tube, also he does not have quick release wheels but rather wing nuts on solid axels.

Also, take a look at his tiny bicycle frame. Judging by the way the top and down tubes merge together at the head tube, this frame is about 48 cm. and still his saddle is low by comparison

Another photo from the 1950s portraying his tiny stature is the one above with Swiss rider Hugo Koblet (Left.) and Robic (Center.) as they pose with World Middleweight Boxing Champ, Sugar Ray Robinson. (Right.)

Another photo from the 1950s portraying his tiny stature is the one above with Swiss rider Hugo Koblet (Left.) and Robic (Center.) as they pose with World Middleweight Boxing Champ, Sugar Ray Robinson. (Right.)

Tragically Jean Robic died in a car crash in 1980; he was still at a relatively young age of 59.

A monument to this little giant stands on the Côte de Bonsecours, in France, and of course, it depicts him wearing his trademark leather helmet.

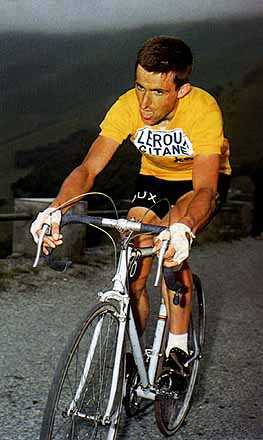

Update July 21, 07: (Picture left.)

From the 1953 Tour de France. Stage winner and Maillot Jaune on Stage 11. Robic riding for a regonal team, was viciously attacked by a jealous French National Team on Stage 12, and a crash victim on Stage 13.

Robic crashed heavily while descending the Col du Fauredon, hitting his head and suffering a concussion. He was unable to start and abandoned the race the next day.

Picture from The Wool Jersey. My thanks to Aldo Ross for all the WJ pictures.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |