Fiorenzo Magni: 1920 – 2012

Mon, October 22, 2012

Mon, October 22, 2012  Italian cyclist Fiorenzo Magni died early last Friday morning; he would have been 92 in less than two months.

Italian cyclist Fiorenzo Magni died early last Friday morning; he would have been 92 in less than two months.

Often referred to as the “Third Man,” because he raced in the late 1940s, early 1950s with the other two Italian greats, Fausto Coppi and Gino Bartali.

Sometimes on the same national team, sometime rivals, Magni was capable, and often did, beat the other two.

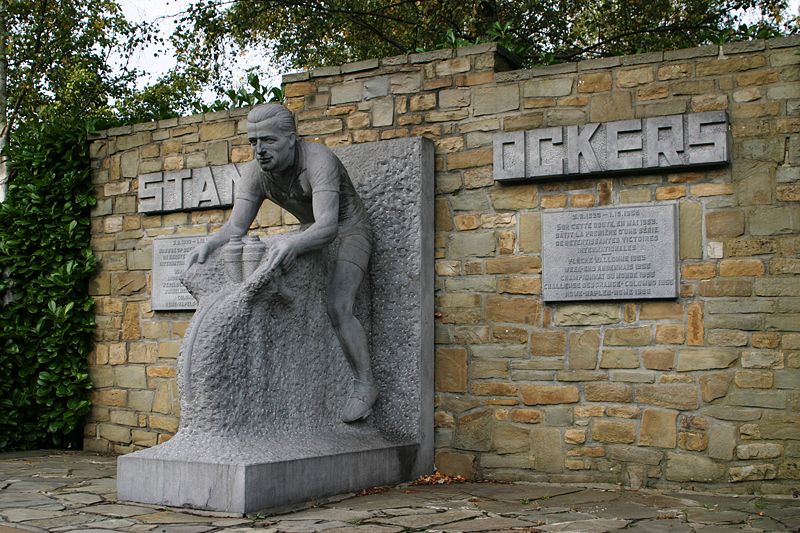

In a period when the sport was less globalized, he won the Tour of Flanders three consecutive years in 1949, 50, and 51. At that time the second non- Belgian to do so.

The press named him, "The Lion of Flanders." He won the Giro d’Italia three times, the last time in 1955 at the age of 35, which to this day stands as a record for the oldest person to win the Giro.

This era is sometimes called the “Golden Age of Cycling.” In the decade following the end of WWII, cycling was the main sport on the European Continent with Italy, France, Belgium and Switzerland being the main players.

Italy had been on the other side during the war, so there was little love lost between Italy and the other countries. But all these nations had suffered a terrible beating, and the exploits of these great riders once again instilled national pride.

I started racing in 1952 so Fiorenzo Magni was one of my heroes, Just as today’s teen racing cyclists would follow the likes of Phillip Gilbert, Tom Boonan, Bradley Wiggins, and Taylor Phinney.

I started racing in 1952 so Fiorenzo Magni was one of my heroes, Just as today’s teen racing cyclists would follow the likes of Phillip Gilbert, Tom Boonan, Bradley Wiggins, and Taylor Phinney.

On rare occasions I got a glimpse of my heroes in action in black and white news reel footage, but mostly I just read about them, and studied photographs.

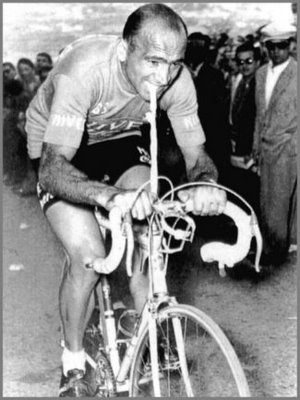

Surely one of the most famous photos of Magni is the one at the top of this piece; he had fallen in the 1956 Giro d’Italia and broken his collar bone. He refused to quit the race, reason being, this was to be his last Giro a race he had won in 1948, 1951, and 1955.

He would rather suffer the immense pain of a broken bone, that to give up on the last opportunity he would have to finish a race that was obviously dear to his heart. The photo shows Fiorenzo with a piece of inner tube around his stem which he held in his teeth because he could no pull on the handlebars due to his broken clavicle.

The amazing end to this story is that Magni not only finished he placed second in the General Classification, beaten only by a younger Charly Gaul, incidentally one of the greatest climbers of all time. How could such courage not go unnoticed by a young cyclist like myself? Fiorenzo Magni taught me a valuable lesson in life; push on, never give up.

Later in more recent years, while researching to write about him here on this blog, he taught me another lesson. This time one of humility.

Let one’s achievements speak for themselves, while accepting life’s disappointments, and realizing that this is the way it was meant to be.

I speak of the 1950 Tour de France. Magni won the Giro three times but the TDF eluded him. Magni was wearing the yellow jersey when the Italian team pulled out en masse after Gino Bartali was threatened by French supporters on the Col d’Aspin.

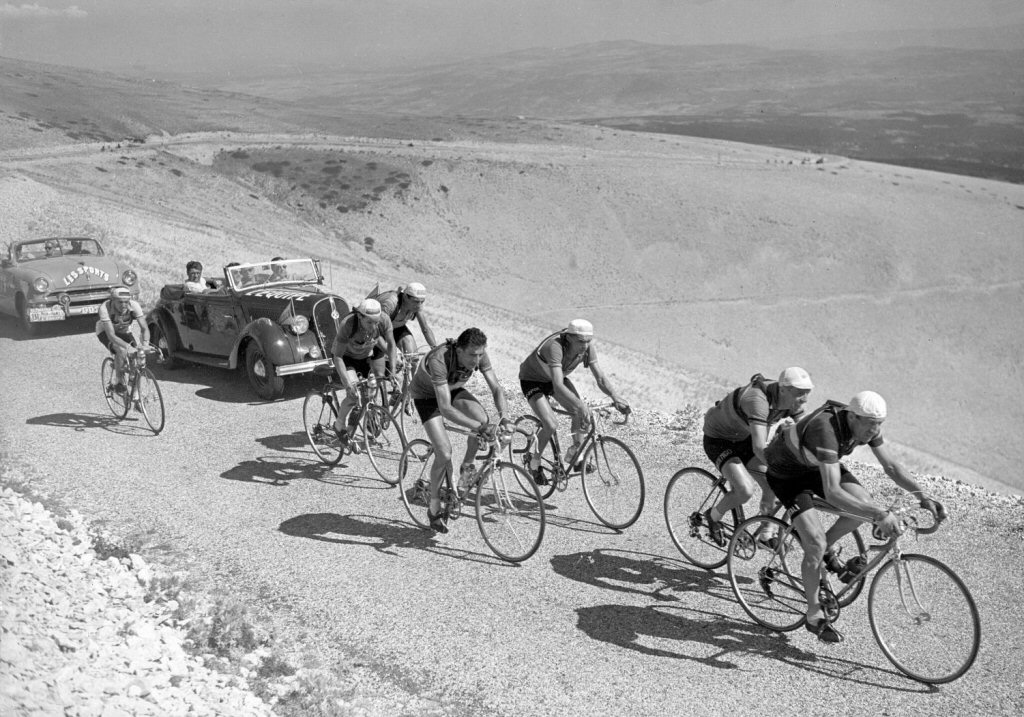

In an era of national teams, and with Fausto Coppi in his prime, Magni would never again have such an opportunity. (Magni leads Coppi, picture below.)

In recent years he spoke of the 1950 Tour in an interview:

Of course I felt bad about that but I believe that there are bigger things than a technical result, even one as important as winning the Tour de France.

Team manager Alfredo Binda and the Italian Federation made the decision, on Bartali's suggestion. I stuck to the rules and accepted their decision. In my life, I have never pretended to have a role that was not mine.

When asked did he feel he could have won the Tour? His reply was:

That's another story. Hindsight is easier than foresight! I think I had a good chance of winning. But saying now that I would have won would not be very smart.

Rest in peace, Fiorenzo Magni; you will be remembered by me and many others I’m sure.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Impossible Dreams

I’ve spent the last couple of days reflecting on Bradley Wiggins win in the Tour de France, with another British rider, Chris Froome (Albeit born in Kenya.) in second place. Considering there has never been another British rider on the podium before, this is a huge deal.

I thought back to over 60 years ago when I started racing in 1952. I had got my first lightweight bike two years previously when I was 14 years old. I could ride a hundred miles easily, but couldn’t race until I was 16.

So soon after my 16th birthday early in February 1952 I was as fit as a butcher’s dog, and chomping at the bit to go. I won my first club event, a 25 mile time trial. The older more seasoned riders had barely been training for a month at that time, whereas I had ridden right through the winter months.

People started telling me I was good and had great potential; something I had never experienced before in my entire life, no one had ever said I was good at anything. I loved it, I lapped it up, and cycling was my whole world.

The Tour de France was the big event of the year for me even back then. There was no live broadcast on television at that time; even if we had owned a TV. I did get to see a black and white film of highlights from the 1952 Tour when Fausto Coppi won. This was pretty wonderful, I saw it at the annual Bike Show at Earls Court in London.

I would order the French cycling publications, But et Club (Above.) and L’Equipe; these would arrive in the mail about a week after they were published, and through the magic of these often full page photos, sometimes a double page spread; I got to know all the giants of cycling.

In the naivety of my youth I began to dream of one day riding the Tour de France and even winning stages with a long solo break-away. I think this fantasy lasted about a year, when reality set in. In 1953 England’s top time-trialist was Ken Joy, who held competition record for 100 miles in 4 hours, 6 minutes was invited to ride in the Grand Prix des Nations.

This event took place in France, and was considered the unofficial world time-trial championship. There was no World TT Championship at that time. There was much speculation as to how well Ken Joy would do; the event was 142 km, just over 88 miles. We knew Joy could do a 4h, 6m. hundred, so he must be in with a chance.

The event was won by a then unknown 19 year old French rider named Jacques Anquetil. Not only did he beat Ken Joy, he started 16 minutes behind the British rider and caught and passed him. A nineteen year old kid, just two years older than me, had trounced the best that Britain had to offer.

Britain was in its own little world back then when it came to cycle racing. France and the rest of Europe was only a short boat trip across the English Channel, but it might have been half a world away, when it came to the class of racing and the level of competition.

Britain is at a disadvantage anyway when you consider there are no big mountains like the ones in central Europe. But if the only racing available to British cyclists are time-trials held on the flattest courses you can find; avoiding what hills you do have. It is hardly conducive to producing world class riders.

Plus there was no road racing on the open roads in the early 1950s; with the exception of those run by the British League of Racing Cyclists (BLRC) a small group of “Rebels” who had broken away from the National Cyclist Union (NCU) the then British governing body for cycling in the UK.

Road racing was not banned by any law or government decree; but was upheld by the amateur officials of the NCU along with the Road Time Trials Council (RTTC), because the status quo, and their piddling little time-trials suited them. It took a lot of balls for a small group of cyclists, lead by Percy Stallard, in 1942 to say fuck you, we’ll hold our own road races.

The BLRC drug British cycling out of the dark ages, and is the main reason the UK finally has a winner of the Tour de France. From 1948 on, the BLRC entered a team in the Warsaw, Berlin, Prague stage race. This was held behind “The Iron Curtain” and was known as the Peace Race.

In 1952 Scottish rider Ian Steel, who had won the BLRC’s first Tour of Britain race a year earlier, won the Peach Race. This lead to partial recognition of the BLRC by the UCI. The NCU tried to block the vote and walked out of the UCI meeting in protest.

What Percy Stallard and the BLRC did was to alert the UCI that there was a problem within British cycling; the NCU (In cahoots with the RTTC.) was acting in its own self interest and not that of the sport. The UCI had told the NCU to settle its differences with the BLRC or the UCI would recognize the BLRC as the British governing body.

Thus the NCU was forced to amalgamate with the BLRC in 1959 to become the British Cycling Federation (BCF) now British Cycling. The ban on road racing was also lifted at that time, and not a moment too soon. Had it waited until the late 1960s or 1970s it probably wouldn’t have happened because of the interests of the motoring public.

So does it surprise me that it is 60 years since my own “Impossible Dreams” of Tour de France participation, that we finally have a British winner? Not really when I think of all that went before. Percy Stallard died in 2001 a bitter man, and rightly so. He was shafted by the BCF, unrecognized and not asked to manage any international teams; even though he had proved himself as a manager in the Peace Race.

I do hope those early BLRC pioneers will now get the recognition they deserve. Because with all the hard work put in by Bradley Wiggins, Chris Froome, and the whole Sky Team. With all the money put in and the efforts of British Cycling; it still would have not happened, because there would still be no road racing in the UK, had it not been for Percy Stallard and the BLRC.