Rik Van Steenbergen: Road Sprinter Supreme

Wed, July 29, 2009

Wed, July 29, 2009  Anyone who followed this year’s Tour de France could not help be impressed with the multiple stage wins by Britain’s Mark Cavendish; together with the overwhelming Team HTC Columbia support.

Anyone who followed this year’s Tour de France could not help be impressed with the multiple stage wins by Britain’s Mark Cavendish; together with the overwhelming Team HTC Columbia support.

Winning the Tour de France is all about climbing ability, and because of this history tends to forget these great individual stage victories.

People know names like Fausto Coppi, Gino Bartali, and Louison Bobet, all great climbers from the late 1940s and 1950s; a period often refered to as "The Golden Age of Cycling."

But who were the great road sprinters of that era, taking most of the bunch finishes? One that springs to my mind was Belgian rider Rik Van Steenbergen.

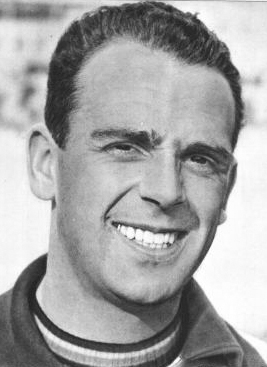

A big man, 6’ 3” 183 lbs, (190.5 cm 83.18 Kgs.) he had a long professional career that began in war torn Belgium in 1943 and lasted until 1966, Van Steenbergen won 270 times on the road, including 3 World Road Championships, in 1949, 1956 and 1957, all taken in sprint finishes.

He won the Tour of Flanders in his first year as a professional at age 18. He won the same event in 1944 and 1946. The Paris-Roubaix in 1948 and 1952, the Flech-Wallone in 1949 and 1958, Paris-Brussels in 1950, and the Milan-San Remo in 1954.

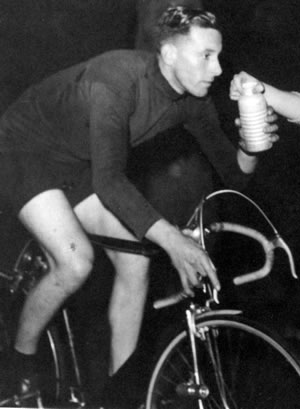

(Above.) Rik Van Steenbergen uses his explosive sprint to win the 1954 Milan-San Remo followed home by Anasti, Favero and Coppi.

(Above.) Rik Van Steenbergen uses his explosive sprint to win the 1954 Milan-San Remo followed home by Anasti, Favero and Coppi.

Van Steenbergen like many great road sprinters was a prolific winner on the track, a total of 715 times including 40 six-day wins. He rode year round, road events spring and summer, and six-day events through the winter.

In spite of this non-specializing he took 15 stage wins in the Giro d’Italia in five appearances, and 4 TDF stage wins in three appearances.

His best Giro result was in 1951 when he finishes second overall behind Italy’s Fiorenzo Magni, beating no less than Ferdi Kubler and Fausto Coppi into 3rd and 4th places respectively. Pretty impressive for a sprinter who couldn’t climb.

Perhaps one of Rik Van Steenbergen’s greatest victories was his 1952 Paris-Roubaix win. With 40 Km. to go the Belgian rider was in a group 50 seconds down on a three man break, consisting of Coppi, Kubler, and Jacques Dupont.

On a 5 Km cobble-stone section of the course Van Steenbergen attacked solo out of the chasing group and miraculously bridged the gap.

On a 5 Km cobble-stone section of the course Van Steenbergen attacked solo out of the chasing group and miraculously bridged the gap.

Towards the finish, Coppi attacked again and again. Kubler was dropped, Dupont punctured, but Van Steenbergen managed to hang on and in the final sprint beat Coppi easily.

The world may never see such a versatile rider again. He was immensely popular; born in 1924 he died in 2003 at age 78 after a long illness.

His funeral was attended by a veritable who’s who of cycling, including Eddy Merckx, Rik van Looy, Roger De Vlaeminck, Walter Godefroot, Johan De Muynck, Lucien van Impe, Freddy Maertens and Briek Schotte.

Also attending were the UCI president Hein Verbruggen and Belgian prime minister Guy Verhofstadt

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |