The Redheaded Stepchild

Thu, March 25, 2010

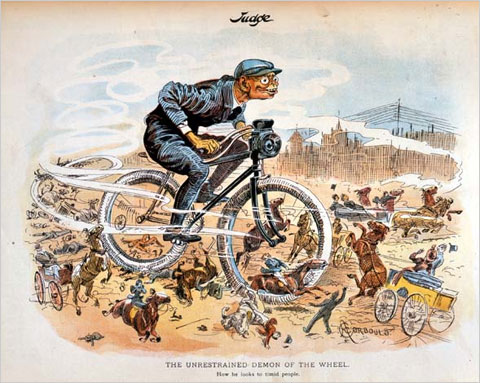

Thu, March 25, 2010 Cyclists have always been society’s “Redheaded Stepchild;” unloved and abused throughout history. The above picture is titled, "The Unrestrained Demon of the Wheel,” published in “The Judge,” Sept. 23, 1893, reflects the attitude of the day.

Since the invention of the ordinary, or high-wheeler in the late 1800s, when horse drawn carriages were the transport of the day. It was the wealthy classes who owned carriages, and bicycles scared the horses.

It was not uncommon for a coach driver to lash out at a passing cyclist with his horsewhip, and pedestrians were not above putting a walking stick through a rider’s wheel.

Bicycles were expensive and initially cycling was a sport of the wealthy, but it was a young man’s pastime and even wealthy young men were viewed with disdain by the older generation.

Cycling was initially banned in places in England as being too dangerous. However, being a “rich man’s sport,” the ban was short lived. By 1880 there were 213 established cycling clubs in the UK. Remember, this was before the invention of the “Safety Bicycle” in 1885, and the pneumatic tire in 1888.

With the invention of the “safety” bicycle, and mass production that followed, it really changed the face of the sport, and people’s attitude to it. Cycling became affordable to the working classes and it quickly became both a pastime and a mode of transport of the masses.

In England the wealthy who lived on large country estates, suddenly found their space invaded on the weekends by the working classes on their bicycles as they ventured outside the cities for the first time to explore the countryside.

Cycling was no longer a pastime for the wealthy, in fact to ride a bicycle was now a definite sign of being lower class.

The privileged upper classes looked for new ways to reclaim the highways again; of course, they found it in the form of the automobile.

However, the resentment towards cyclists, by the upper classes, was already established long before the automobile arrived.

The invention of the pneumatic tire meant there was an explosion in the sport of cycle racing. And nothing will disrupt a quiet Sunday drive to church by the local gentry, like a bike race. This led to a ban in England of mass start road racing in 1894; a ban that would last until the 1950s.

The result was road racing never developed in the UK as it did in the rest of Europe. In countries like France, Holland, Belgium, and Italy cyclists receive respect and toleration because of the popularity of cycle road racing in those countries. The general public on the continent of Europe has become used to seeing cyclists racing and training on the highways.

The only competitive events open to British cyclists were track racing, of course limited to those close to a track. A few mass start circuit races in private parks, and individual time trials, which would become the mainstay of British cycling competition.

It is interesting to note that in 1894, as road racing was banned in England as being too dangerous; the first motor race was held on public roads in France. This led to almost ten years of absolute carnage as racecars quickly developed to reach speeds of 100 mph (Without the brakes, steering and road surfaces to match these speeds.) and there was wholesale slaughter of both spectators and drivers.

The attitude of the wealthy was no doubt one of, what were the deaths of a few of the peasant class, as long as they could enjoy their sport? Much the same state of affairs existed in the United States; it was the privileged who initially drove cars. They set the rules of accepted behavior and attitudes, which still exist today.

Is this not still the attitude now? “What is the death or injury of a few, as long as I can drive as fast as I like, and in a manner that suits me?” Of course, no one intends for people to die, but behave in a certain way and the inevitable will happen. And if a cyclist or pedestrian gets hit, no real concern, just the question, “What were they doing on the road anyway?”

When Henry Ford made cars available to the masses, naturally they expected to drive to the same standards set by their wealthy predecessors. All road safety legislation since has been aimed at protecting the person inside the car, with little thought going into the protection of other road users, namely pedestrians and cyclists.

Those of us today exercising our rights by riding our bike on the public highways should not despair. However, we should be realistic and recognize that current attitudes of the general public have been formed over a 100 years, or more; change will continue, but slowly.

In the mean time we will remain the redheaded stepchild, and should expect the abuse to last a little longer.

Footnote: This article was first posted on October 19th, 2007, I thought it was worth repeating, with the addition of the picture at the top