More questions than answers

Thu, April 21, 2011

Thu, April 21, 2011 After my last article about Cornell University’s bicycle experiment, I started thinking “What if” the bicycle had never been invented in the late 1800s, would engineers come up with a similar design today?

Even if they did, I doubt it would be taken seriously as a viable form of personal transport.

The bicycle came into being at a time when the only other form of personal transport was the horse. These animals were not only expensive to buy, they needed feeding and housing; working class people could not afford horses.

However, once the bicycle had been invented, and a few years later mass production put this new machine within reach of the poorer classes it became a revolutionary form of personal transport. Many forget that the automobile came later and eventually replaced the horse as the wealthy person’s transport of choice.

So what if the automobile had come first. The poorer working classes would have continued living in cities where they could get to work either on foot or by rail or other form of public transport.

The bicycle had less of an impact on America’s history, because there it was the automobile that became affordable due to mass production, and the luxury of plenty of space led to urban sprawl, and the suburbs.

In the UK and other smaller European countries, it was viable for a working class man to live in a rural area, and cycle 5 to 10 miles to work each day. The humble bike was the working man’s wheels all the way up to the late 1950s, early 1960s.

Even though commuting to work by bicycle is a hard sell today for the majority, think how much harder it would be if engineers were only just developing the bicycle now. Almost everyone can at least ride a bicycle, and most households have at least one bike in their garage.

Look what happened in Japan recently after the earthquake and tsunami? People took to bicycles to get where they needed to be. How high will gas prices need to go before some people in the UK and the US start to realize their choice might be eating, or putting gas in the car, and bicycles will start to be dragged out of garages?

Would today’s engineers even think of a two-wheeled vehicle? If there were no bicycles there would be no motorcycles, only four wheel vehicles; don’t forget the first autos were “Horseless Carriages.”

Above: A German Draisine or Laufmaschine, circa 1820. I have always called this a Hobby Horse.

Above: A German Draisine or Laufmaschine, circa 1820. I have always called this a Hobby Horse.

In my last article I referred to the Cornell experiment as a “Push Toy.” I realized later, had it not been for a push toy, the bicycle would have never come into being?

The bicycle’s predecessor, the Hobby Horse came on the scene in the early 1800s as a rich man’s whimsical plaything,

It only needed two wheels because its rider kept his feet on the ground.

It only needed two wheels because its rider kept his feet on the ground.

No doubt it was soon discovered that its rider could lift his feet clear of the ground and remain balanced when coasting downhill.

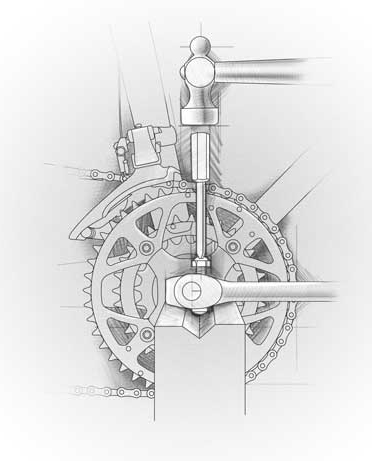

What has always amazed me is that it took until towards the end of the 1800s for someone to attach a simple foot crank to the front wheel and it became a bicycle.

I started out by mentioning that before the bicycle the only form of personal transport was the horse. I am sure ever since men rode horses, children pretended to ride horses with a stick between their legs.

When the wheel was invented, model horses with wheels were made as children’s toys, from this came the adult version in the 1800s, and from that the bicycle. The bicycle evolved, rather than it was invented; it was certainly not invented by any one person.

It is one of the simplest and most efficient machines that humankind has ever made. What I find surprising is that today almost 200 years later, engineers are still asking, “How does its rider balance, and how does it steer?” The bicycle still raises more questions than answers.

I for one doubt very much that today’s engineers, even knowing about gyroscopic precession, caster action and such, would even think of building a two-wheeled vehicle for personal transport. So I am glad that the bicycle came first and then the automobile, it may not have even happened the other way round.

What do you think? Just a little food for thought for you to munch on.