Old bike designs die hard

Fri, June 5, 2009

Fri, June 5, 2009  In my previous post I wrote how the High-wheeler or Ordinary bike influenced riding habits well into the next century. It also influenced frame design into the 1950s and 1960s.

In my previous post I wrote how the High-wheeler or Ordinary bike influenced riding habits well into the next century. It also influenced frame design into the 1950s and 1960s.

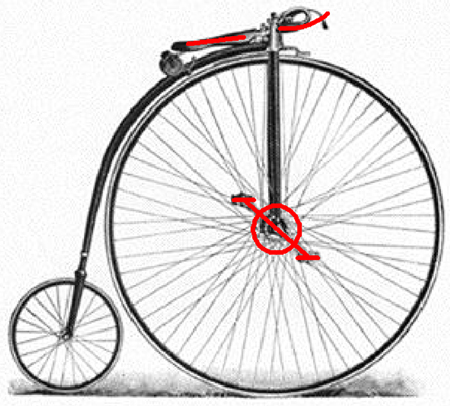

If you look at the top picture you can see, due to the simplistic design of these old bikes, there was a limitation where the rider could be placed. I have drawn in red the three points of contact; the saddle, pedals, and handlebars.

With the steering almost vertical, the handlebars are directly above the pedals. If you can imagine on a modern bike if the handlebars were directly above the bottom bracket, they would be about where the nose of your saddle is.

So you can appreciate that if this were the situation, the rider would have to sit much further back. This was the case on the old ordinary bikes the riders were sitting much further back than we do today.

People do not like change, and as I mentioned in my last piece the cycling enthusiast did not take to the new fangled “Safety” bicycle immediately. It was necessary for those designing the new machine to place the rider in a position he was familiar with.

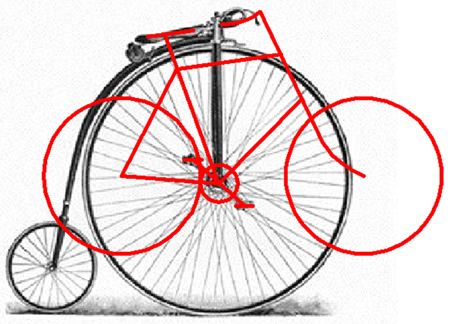

In the next picture I have drawn a safety bicycle superimposed on the ordinary. I left the saddle, pedals, and handlebars exactly where they were on the high-wheeler. By placing a front and rear wheels in the only logical place, and connecting all the dots, you can see we have a close approximation of a early safety bicycle.

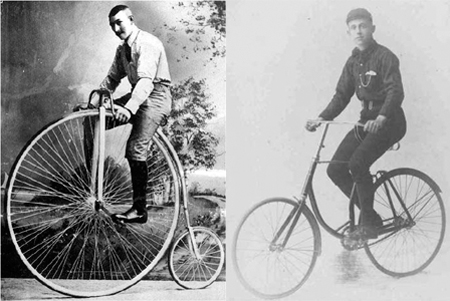

This theory is confirmed by the photos below, showing two riders in almost identical positions; one on an ordinary and one on a “Rover,” the first safety bike.

The next picture below is of Ottavio Bottecchia's bike; an Automoto that he rode to victory in the 1925 Tour de France. In 25 or 30 years the handlebars have been moved forward and lowered, but the saddle position in relation to the pedals has remained as it was on the ordinary. The seat angle is about 68 degrees.

The picture below is of Louison Bobet’s French made Stella that he rode to his 1954 Tour de France win. The angles have become slightly steeper and the fork rake is shortened. However, look at where the nose of the saddle is in relation to the bottom bracket.

This was the way bikes were designed when I started racing in 1952. I was always told by my elders that I had to sit back in order to pedal efficiently. In time I questioned this because I am somewhat short in stature, and found when making maximum effort, I would slide forward and end up sitting on the nose of the saddle.

Studying photos of other riders I could see many had the same problem, this is what started me experimenting with frame design. Initially I was just looking to improve my own performance.

The problem has always been that in general, people who race bikes do not build them, and people who build bikes do not race them. And no one ever questions why certain aspects of design are the way they are.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

The picture above is of me riding in the National Championship

The picture above is of me riding in the National Championship