Aldo Ross’s Pic of the Day

Thu, January 31, 2008

Thu, January 31, 2008 As a teenager in the 1950s one of the highlights of my year was during the Tour de France when I would order copies of a French sports paper called “Le Miroir des Sports.”

It would arrive in the mail, a newspaper size publication printed on glossy paper. All in French so I couldn’t understand the captions, but I didn’t need to, I could pick out the riders names and the photos themselves told the story.

Over the years my copies got lost, then some time ago I discovered bicycle history enthusiast Aldo Ross has a large collection of these papers. Most people with such a collection would keep them to themselves, but Aldo Ross generously shares these images by posting what he calls his “Pic of the day” on the Wool Jersey site.

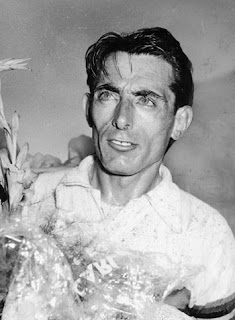

I use the word “generously” because scanning and posting these pictures is a time consuming exercise. The pictures give me a great deal of pleasure, especially when occasionally I will remember a picture from my youth. Like the one below of Swiss rider Hugo Koblet on his way to his 1951 Tour win.

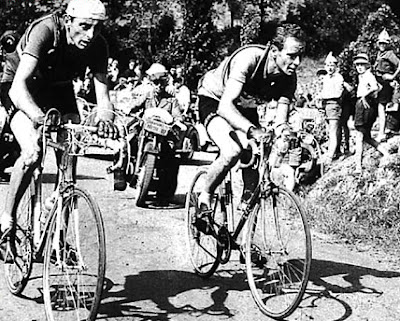

You can see from the picture, the road conditions were atrocious, and punctures were a frequent occurrence. Race regulations back then did not allow a wheel change and Koblet’s team is changing the tire. These are tubular tires, glued to the rim.

Often the riders changed their own tires if their mechanic was not close at hand. You can see the spare tire laying at Koblet’s feet; this was probably wrapped around his shoulders, which was a typical way to carry a spare back then.

A second spare tire is neatly folded and strapped under his saddle. Incidentally, that is probably a Brooks B17 leather saddle; I say that because almost the entire Tour de France field rode on a B17 during that era.

Koblet’s bike has a regular pump in front of the seat tube, and a CO2 pump behind it. (Yes, we had CO2 pumps back then.) The bike has steel cottered cranks with Simplex rings. It has early Campagnolo front and rear derailleurs, operated by bar end shifters. (Not shown in this picture.)

There is no derailleur hanger, the gear is clamped to the rear dropout, and there were no braze-on cable stops. The bike has a full length cable from the handlebar gear lever to the rear derailleur, held to the frame with clips. There are fender eyelets on the rear dropouts; this bike would be used for racing and training. Koblet’s eyes are focused down the hill, looking to see who is coming up. He was probably leading when he punctured; tall and slender, he has the ultimate climber’s build. He is reaching in his pocket for food, it is almost impossible to eat on a climb like this, so a rider would use a forced stop like this the grab some nourishment. Note that the jersey has front pockets as well as rear, and these are also stuffed with food.

Koblet’s eyes are focused down the hill, looking to see who is coming up. He was probably leading when he punctured; tall and slender, he has the ultimate climber’s build. He is reaching in his pocket for food, it is almost impossible to eat on a climb like this, so a rider would use a forced stop like this the grab some nourishment. Note that the jersey has front pockets as well as rear, and these are also stuffed with food.

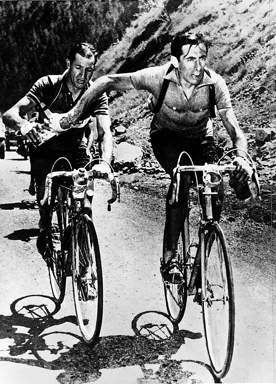

Another puncture in this next picture; (Right.) Koblet is now wearing the race leader’s Yellow Jersey. Even though the picture is not in color I know it is the Yellow Jersey because it has the initials HD embroidered on the chest, for Henri Desgrange, founder of the Tour de France who died in 1940.

Again, his face stuffed with food, Koblet checks his watch to see how much time he has lost. In the final picture, Koblet has a spare tire crossed behind his back and looped around his shoulders. He has his goggles on his arm, as his pockets are no doubt full of food. Because he has a pump on his seat tube, a second water bottle is mounted on his handlebars.

In the final picture, Koblet has a spare tire crossed behind his back and looped around his shoulders. He has his goggles on his arm, as his pockets are no doubt full of food. Because he has a pump on his seat tube, a second water bottle is mounted on his handlebars.

Plastic water bottles have not yet arrived, these were made from spun aluminum, with a real cork for a stopper.

There are more pictures from Hugo Koblet's 1951 Tour victory on Aldo's page here.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |