Twiddling

Mon, November 26, 2007

Mon, November 26, 2007

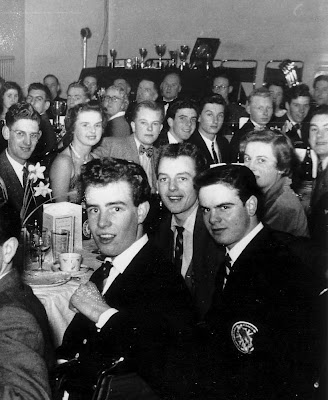

Two important passions in my life have been music and bicycles. Coming of age as I did in the early 1950s, musically, I came in at the end of the Big Band era.

I saw the American big bands like Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Stan Kenton when they toured the UK. Later I witnessed the birth of Rock n' Roll in the mid 1950s and experienced first hand the emergence of the British music scene in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

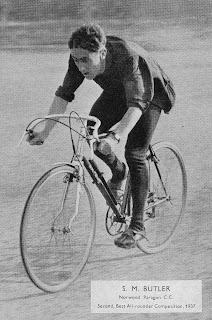

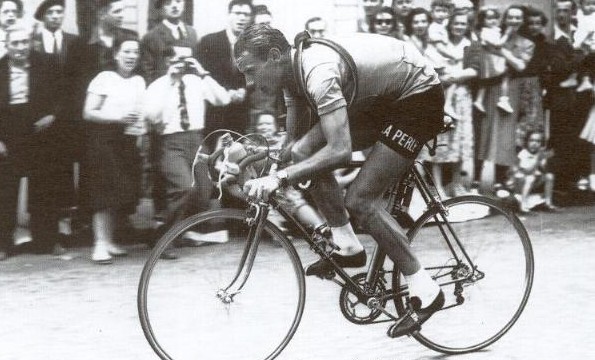

As for cycling I came in at the end of the fixed wheel era. In the early 1950s all the top time-trialists in the UK rode fixed gear. The picture above from 1948 shows a typical British time-trail scene.

Not a car in site; it is easy to see why this era is often referred to as “The Golden Age of Cycling.” Note the rider has a fixed gear, a single front brake, and the obligatory bell on the handlebars. (Picture from Classic Lightweights UK.)

Time Trialing in the UK during that period was predominantly a working class sport, and many working class people at that time did not own cars. Their bike was not only their recreation and sport, but also their mode of transport to get to work each day. Most had a bike with track dropouts making for easy adjustment of chain tension while switching differing size fixed rear sprockets.

The bike would have a brazed on lamp bracket boss on the front fork and have eyelets and clearance for mudguards. The mudguards would be put to good use; it rains a lot in the UK, and if your bike is your only means of transport, riding in the rain is your only option. A rider would wear a rain cape (Poncho) that was long enough at the front to reach over the handlebars thus keep their legs dry.

At the weekend, the mudguards would come off in readiness for a time trial and the cyclist would ride to the start of the event often carrying his best wheels with tubular tires on wheel carriers attached to the front of the bike.

These wheel carriers were simply two aluminum strips about 5 or 6 inches long with a hole drilled each end. The front wheel nuts were removed, the metal strips were then attached on either side of the front wheel spindle so they stood above and slightly forward of the front hub. The nuts were replaced and tightened.

The spare front and rear wheel spindle then attached to the hole in the top end of the metal strip, one on either side. Finally, the spare wheels were strapped to the handlebars using a toe-strap. Track nuts were always used, not quick-release. Everyone used a Brooks leather saddle that had bag loops on the rear; a saddle bag would be attached to carry racing clothes to change into, and food.

By today's standards riders used pretty low gears; distance events would be ridden on a 79 to 81 inch gear and the shorter events on about an 86 inch gear. The thinking of the day was that speed was achieved by pedaling fast, known as "twiddling."

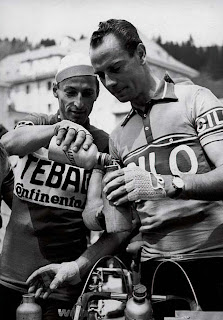

I was like many of the younger riders and used gears, because I emulated the top European pro riders rather than the British time-trialists. However I did switch to fixed gear to ride through the winter months, and I would often strip my bike of its gears and convert to fixed to ride a 10 or 25 mile time-trial.

A very popular early season event was the 72 inch restricted gear 25 mile event. All competitors rode a 48 x 18 fixed gear, which was checked at the start by wheeling the bike between two chalk marks on the road, to ensure the crank did one complete revolution.

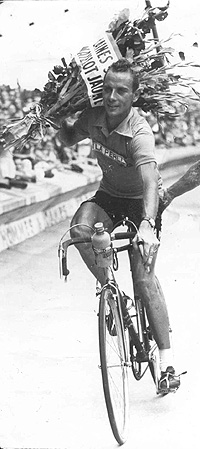

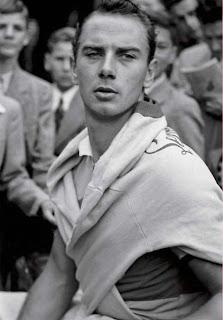

My very first time-trial was such an event, in March of 1952, one month after my 16th birthday. I had put in many miles on a 65 inch fixed gear all through the winter months and I could definitely twiddle. I had been riding seriously for over a year, but had to wait until my 16th birthday to be able to race. I had been preparing for my début through the winter, whereas the more seasoned riders had been taking it easy and had not reached their full level of fitness at the start of the season.

I had been preparing for my début through the winter, whereas the more seasoned riders had been taking it easy and had not reached their full level of fitness at the start of the season.

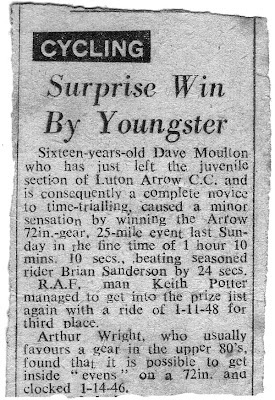

I surprised myself and my fellow club members when I won the event with a time of 1hour-10min.-10sec. (See the press clipping, left.)

This meant I was pedaling at an average rate of over 100 RPM for the 25 miles. Top riders of that era could turn in times under the hour for 25 miles on a 72 inch gear; which is close to 120 RPM average. Two revs per second, that’s some serious twiddling.

The RPM rate was calculated as follows: 25 miles = 132,000 feet. Divide by my time for distance, 70 minutes = 1885.714 feet covered in one minute. Divide by feet covered per pedal revolution (18.67 ft.) = 101 RPM.

Calculated at a nominal wheel size of 26.75 inch diameter. (7.003 feet circumference.) 48 T chainring, divide by 18 T sprocket = 2.666 turns of the rear wheel per 1 turn of the chainring. 7.003 x 2.666 = 18.67 feet traveled per pedal rev.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |