Trail, fork rake, and a little bit of history

Fri, May 4, 2007

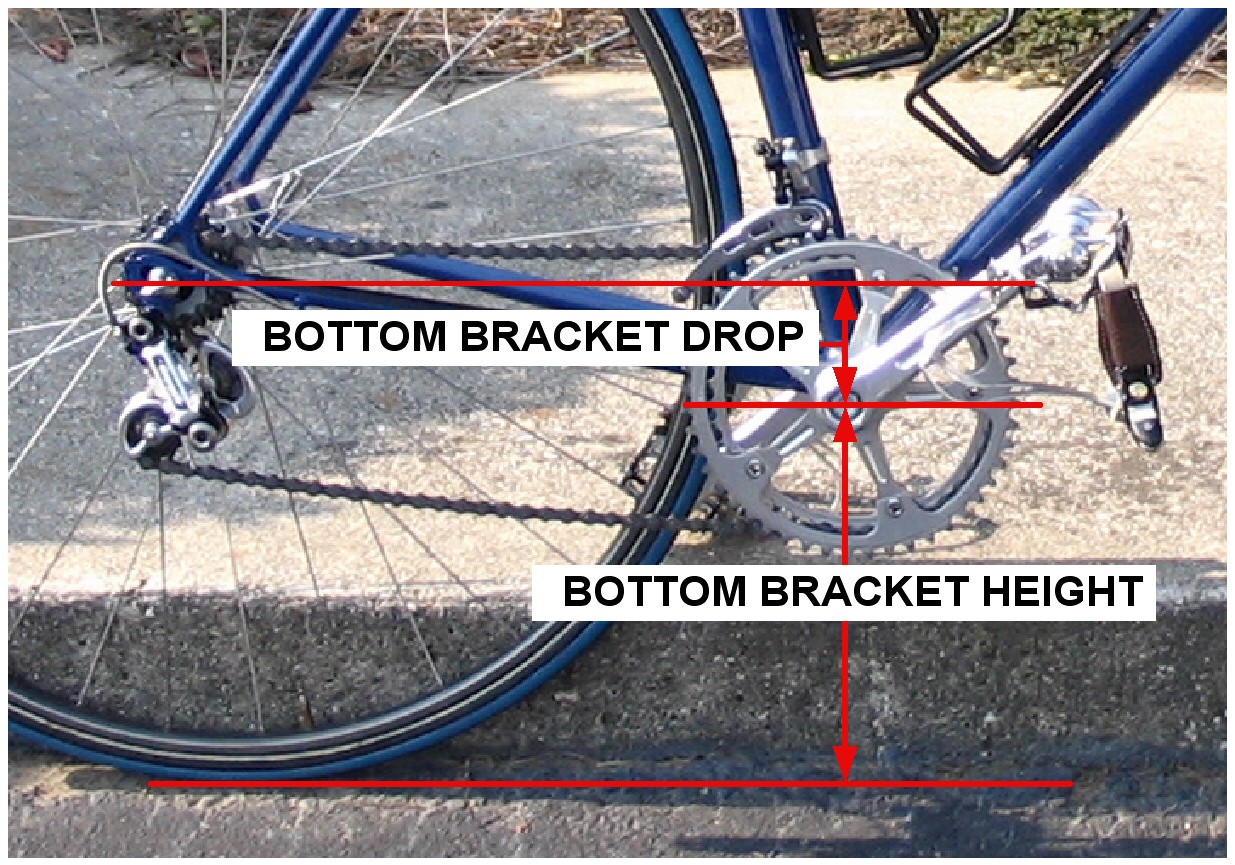

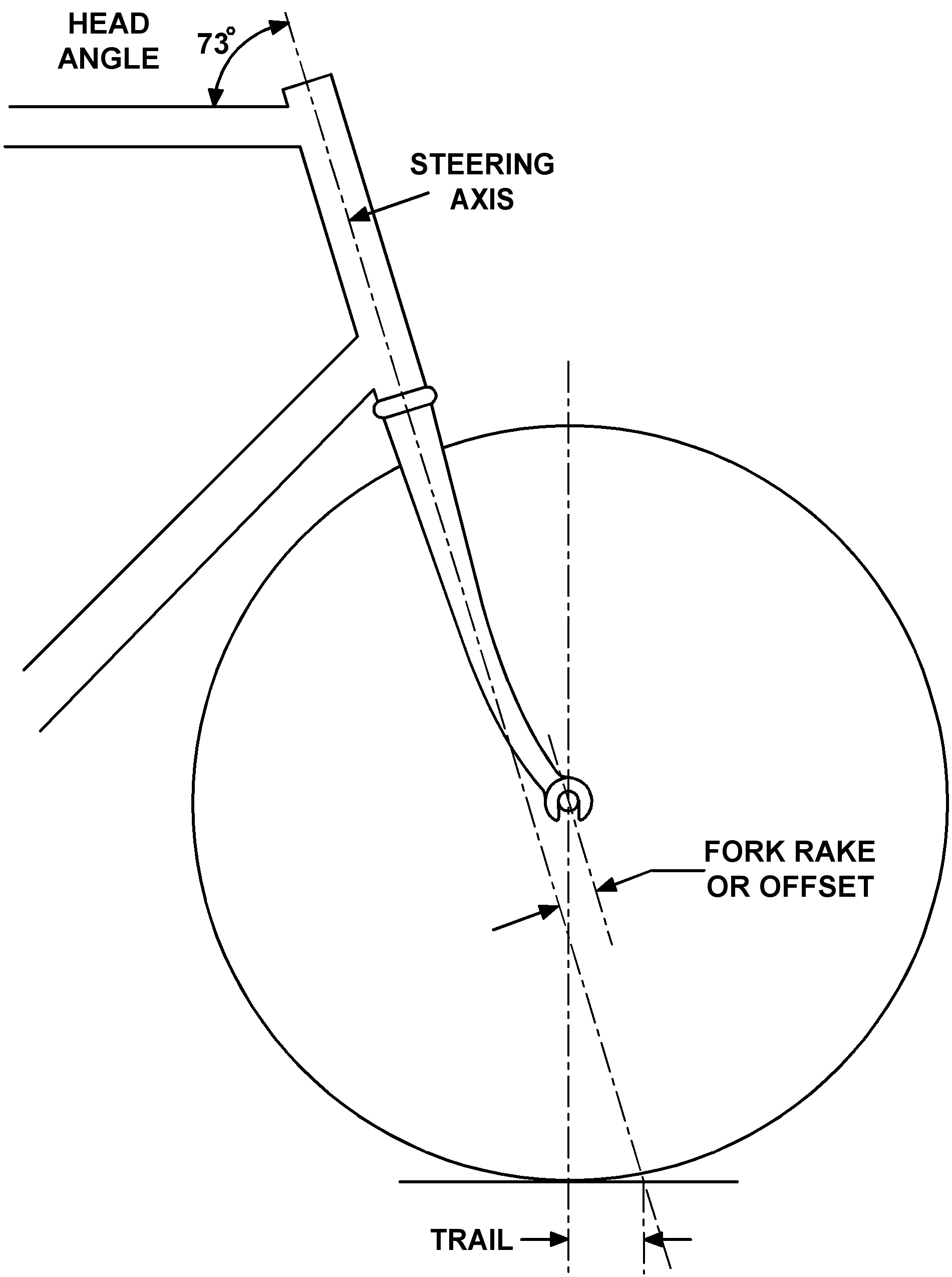

Fri, May 4, 2007  If you draw an imaginary line through the center of your bicycle’s steering tube (Steering Axis.) it will reach the ground at a point in front of where the wheel actually contacts the ground.

If you draw an imaginary line through the center of your bicycle’s steering tube (Steering Axis.) it will reach the ground at a point in front of where the wheel actually contacts the ground.

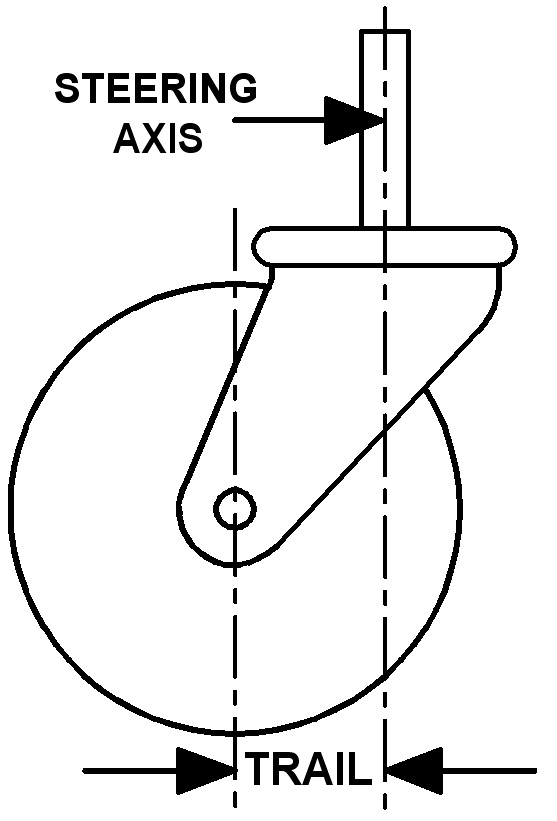

The difference between these two points is known as the trail. Trail assists steering; as you lean the bike to the left or right, the steering axis moves in that direction, and thereby turns the wheel in that direction as it pivots on the point of contact with the road.

Trail also assists the bike in holding a straight line. It works on the same principal as a castor wheel on a grocery cart, which goes in the direction it is pushed. (Or in theory it is supposed to.) This is why it is called “trail,” because the wheel trails along behind the steering axis. Fork rake or offset is the distance between the steering axis and the wheel center. It doesn’t matter if the fork blade is curved forward in the traditional way, or if the fork blade is straight but angled forward from the crown. If the offset is the same the bike will handle the same.

Fork rake or offset is the distance between the steering axis and the wheel center. It doesn’t matter if the fork blade is curved forward in the traditional way, or if the fork blade is straight but angled forward from the crown. If the offset is the same the bike will handle the same.

You will see from the drawing above, if the head angle is made steeper then trail decreases because the steering axis moves closer to the wheel’s point of contact. Conversely, a shallow head angle will lengthen trail.

Less fork rake, increases trail, because the wheel center is moved back away from the steering axis. More fork rake means less trail because the wheel center is moved forward. Bicycles built in the 1930s through the 1950s typically had as much as 3 ½ inches (9cm.) of fork rake resulting in very little trial, often zero. There was a theory at that time that trail made steering heavy and sluggish.

Bicycles built in the 1930s through the 1950s typically had as much as 3 ½ inches (9cm.) of fork rake resulting in very little trial, often zero. There was a theory at that time that trail made steering heavy and sluggish.

I remember writing an article for Cycling magazine in the 1970s; someone wrote to me saying my theories on trail were wrong, and sent me an early 1950s article from Cycling to prove it.

The old theory was that if you had the front wheel’s point of contact behind the steering axis, when the steering was turned 90 degrees the point of contact was then on the steering axis line. Therefore, the front end of the bike had dropped slightly, and to straighten up again, the steering had to lift the weight of the bike and rider; thus sluggish handling.

While this statement is true, in practice when riding, the front wheel never turns 90 degrees. In fact during normal cornering the front wheel turns very little, making this whole theory about the front of the bike going up and down irrelevant.

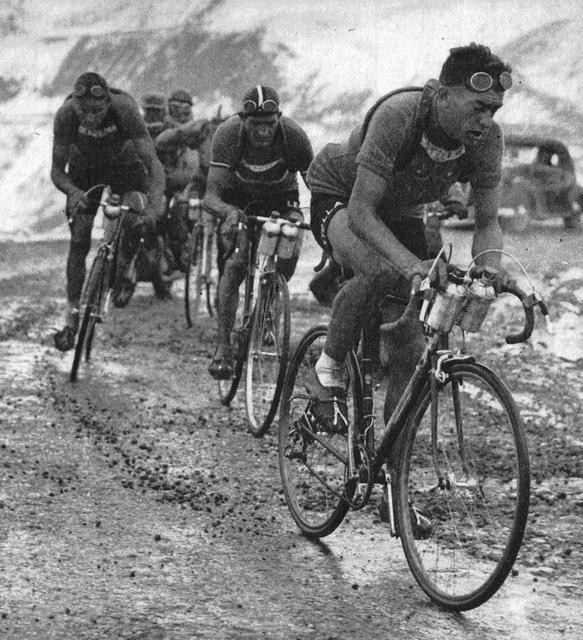

I started racing in the early 1950s and I can say from experience the bikes of that era did not handle and corner near as well as today’s designs. These bikes handled reasonably well because frames were built with much longer wheelbases, wheels and tires were heavier, and tires were fatter.

Road conditions at that time, especially in countries like Italy and France were often appalling. The long fork rake and the long wheelbase had a dampening affect on the rough road conditions.

[Typical European road conditions in the 1940s. Louison Bobet leads Gino Bartali (striped cap) and André Brulé in the 1948 Tour de France. Picture from The Wool Jersey.]

[Typical European road conditions in the 1940s. Louison Bobet leads Gino Bartali (striped cap) and André Brulé in the 1948 Tour de France. Picture from The Wool Jersey.]

As road conditions improved, bikes were built with shorter wheelbases and at the same time tires became much narrower. It eventually became necessary to increase trail to keep the bike going straight.

There was a somewhat chicken and egg situation with regard to shortening wheelbases and adding trail. In my case I shortened the fork rake to shorten the wheelbase and found the resulting increase in trail was an improvement.

Other older established builders, still clinging to the little or no trail theory, shortened the fork rake but at the same time made the head angle steeper to maintain the trail status quo.

This made for some very squirrelly bikes being built in the 1970s, with 75 and 76 degree head angles and front wheels almost touching the down tube. Shorter chainstays to shorten the rear end of the bike were pretty much universally accepted.

A shorter wheelbase means the bike will turn on a tighter radius. Think of a school bus and a compact car, which one will turn tighter? The front wheel turns less on a short wheelbase bike on any given corner; this translates to having to lean less to get around a bend.

I think the big advantage I had was that I was still actively racing and could try out these changes, and experience the difference first hand. Eventually everyone agreed that trail was not a bad thing and head angles became sensible again.

Frames I built had around 2 ½ inches (6.3cm.) of trail. In the early 1970s I did experiment with more trail but found that the bike felt sluggish and had a tendency to wander when climbing or sprinting out of the saddle.

As with any design aspect, more is not necessarily better; for a road bike with a 73 degree head angle the optimum trail seems to be around 2 to 2 ½ inches (5 to 6.3cm.)

Addendum. Nov 15, 2008.

There seems to be some confusion over the term “Fork rake,” which I can understand. The dictionary definition for rake is “The angle of inclination from the vertical.” However, when referring to bicycles, rake and offset are different terms for the same thing. Both are the term for the distance the wheel center is set from the steering axis, regardless of the head angle.

This probably came about because early framebuilders were artisans, not scholars. To add to the confusion, a bicycle head angle is measured from the horizontal, not the vertical. Back in the day when all bicycles had perfectly level top tubes, it was the angle measured from above the top tube to an imaginary extension of the head tube.

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |