With the growing popularity of events like Eroica where vintage bikes must be used with old school toe clips and straps, there is a need to know how to align slotted shoe cleats.

Slotted Cleats for use on modern shoes with a standard 3 bolt system, are available from Yellow Jersey. These cleats only use two of the three screws. The reason being that with this old school system, the strap is what holds the foot to the pedal, the cleat is just there to prevent any fore and aft movement. Therefore two screws are enough and also two screws allow adjustment for angle.

But where do they go, and how do you know they are aligned properly? Well read on and I will explain. When I started racing in the 1950s, cycling shoes had leather soles and the cleats were nailed on. So we had to get them positioned right, there was no such thing as “Pedal Float.”

The slotted cleats were usually made of aluminum and came in a little packet with enough nails to get the job done.

The slotted cleats were usually made of aluminum and came in a little packet with enough nails to get the job done.

Remember this was in the days before God invented Tennis Shoes. (or Trainers in the UK.)

Every household had a shoe repair kit that included a cobblers last, which is a cast iron foot that holds the shoe while you hammer nails in it. (Picture above left.)

The first thing we did with a new pair of shoes was go for a ride without cleats. The toe clips held the foot in place, and after a 20 or 30 mile ride, the pedal would make a mark on the sole of the shoe. This mark acted as a rough guide to where the cleat should be, but there were also a few simple alignment checks that I will pass on.

We nailed the cleat on using just a few nails, then went for a test ride. When we were satisfied the cleats were in the right place, we hammered in the rest of the nails. As usual, my post contains a little bit of history. If we look back at how we got where we are today, often the problems we encountered in the past are a clue to solving the problems of today.

The first thing to do with today’s set up, is clip in your regular shoe to your clipless pedals, and measure from the pedal spindle to the toe. It is important you replicate the same foot position with your old school pedals, as this is what you are used to, and a different position will affect saddle height and other things.

This is shown in the picture above as measurement “A.” Position the slotted cleat so you attain this same measurement. Choose a toe clip that will allow clearance between the toe of the shoe and the inside of the clip.

1/16 to 1/8 inch is ideal, slightly more is no big deal. What you don't want is your toe pressing hard against the inside of the clip. Sore toes will result, and maybe some blackened toe nails. If the clips are too short, they can be packed out with washers or nuts between the pedal and toe clip.

The cleats are aligned as follows. With the shoes side by side, soles and heels touching, the slots in the cleats are in a straight line across both shoes. You could drop a straight edge in the slot. This means when pedaling, the inside of the foot is parallel with the crank arm. In addition, when the two shoes are placed with soles facing, the cleats line up exactly, and you can see clearly through the two slots. (See above picture.)

It is important that both these tests check out. The reason being, let’s say both cleats are rotated slightly in the same direction. The straight edge check across the slots may line up, but when the shoes are placed with the soles facing the cleats will not line up.

Conversely, the cleats could be fitted so the toes are turned in or out slightly. With the soles facing each other the cleats may line up, but when the shoes are placed side by side the cleats will not be aligned straight across. Only when both checks agree are the slots in the cleats at a true 90 degrees to the inside edge of the shoe.

A word about toe straps. Thread the strap through the outside quill plate of the pedal, then through the slot in the pedal frame.

A word about toe straps. Thread the strap through the outside quill plate of the pedal, then through the slot in the pedal frame.

Give the strap one complete 360 degree twist, before treading the strap through the inner pedal plate.

This prevents the strap from slipping. It probably won’t slip anyway, but if you want to be true old school, give it a twist.

There is a little tag thing on the inside of Campagnolo pedals that stops the strap from rubbing on the crank arm. Make sure the strap is inside this little tag. Thread the strap through the toe clip, then through the first spring loaded quick release buckle. But never, repeat never, tuck the end of the strap into the second loop.

Only Trackies tuck the strap in. They have the luxury of a person to catch them when they come to a stop. Roadies just fall over if they can’t undo the strap. Which will happen if the end is tucked in. Leave the end of the strap sticking out, so you can grab it and pull it tight

Even better, if you can find some of these little strap end buttons, you will really be the Dog’s Bollocks.

Even better, if you can find some of these little strap end buttons, you will really be the Dog’s Bollocks.

They give you something to grab hold of when you tighten the strap, they prevent the strap from slipping completely out of the buckle, and your bike is idiot proof so no one can borrow it and tuck the straps in.

Tighten the straps by pulling on the loose end as soon as your feet are in the clips. Before you come to a stop, reach down and flick the buckle open with your thumb. Give the straps an extra tighten as you approach a climb, or if you are about to launch a big attack. But go to the back of the pace-line first so no one sees you.

To Share click "Share Article" below

To Share click "Share Article" below

Wed, September 13, 2017

Wed, September 13, 2017

It wasn’t until freewheels went beyond six sprockets to 7, 8, 9, and 10, that an all in one unit or cassette hub was considered practical.

It wasn’t until freewheels went beyond six sprockets to 7, 8, 9, and 10, that an all in one unit or cassette hub was considered practical.

Drillium and Bottom Bracket Cutouts

Most vintage bike enthusiasts know about cutouts in frame bottom brackets, but some, especially newbies don’t know the reason. Someone recently asked me why I didn’t put drain holes in my bottom brackets? I was baffled and asked, “Who does that?” He listed frames that had “Drain holes,” and I realized he was talking about bottom bracket cutouts.

It was a fashion gimmick of its time, that’s all. There was no logical reason. Think about it, it is a poor drainage system. The bottom bracket is in direct line of fire from water spraying up from the front wheel. These large holes let in more water than they let out again.

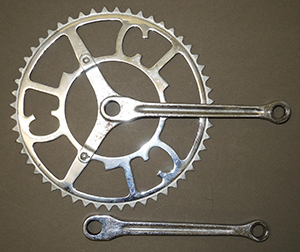

Drilling holes in component parts to reduce weight. The fad was huge in the UK, especially amongst time-trialists, who were forever looking for ways to save weight. And of course removing metal reduces weight.

The amount of weight saved by drilling holes in aluminum components was miniscule, but it didn’t matter.

It was a way to customize a bike and a few more holes than your competitor was a psychological boost if nothing else.

Component manufactures were quick to follow this trend, and for example, a seat post that was previously round and smooth, now had flutes machined in them. Frame builders too got on the band wagon. A large hole cut out of a bottom bracket shell, was a considerable chunk of steel that was no longer there.

Of course all these holes and flutes created more aerodynamic drag, but no one thought of that at the time. Aero bikes would be a future craze.

Frame builders used a special die and a press to stamp out these cutouts in seconds. Holes were similarly stamped in lugs before the frame was assembled. It also gave framebuilders an opportunity to individualize frames with cutouts in the form of their logo. It was done for brand recognition.

My newbie inquisitor was still not satisfied. “If these are not drain holes in the BB, then why weren’t they engraved?” I’ll tell you why. Holes can be stamped out in seconds, but engraving takes time, and is super expensive. Especially engraving on a curved surface.

It had to be done with a special fixture that rotated the shell as the engraving progressed, so the router bit that does the cutting is always at right angles to the curved surface of the BB shell. (Picture right.)

It is a highly skilled operation and is one of the reasons my custom frames cost so much. If you see what appears to be engraving on the bottom bracket of a production bike. Things like lettering, a logo or grooves. It was most likely cast that way. The design was in the mold.

Just as my custom frames had my logo engraved in the crown, whereas my production Fuso frame had the name cast in it. (See above.) I had to buy 1,000 crowns to get that feature. So why did my Fuso not have a cutout BB? By 1984 when production on the Fuso started, the fashion had run its course.

Some Italian framebuilders continued doing cutouts, but remember they had dies to stamp the holes. I was not about to invest that kind of money for the tooling and a press, for fad that had run its course, and was dying out anyway.