Climbing out of the saddle

Tue, August 13, 2013

Tue, August 13, 2013

Climbing a hill out of the saddle, standing on the pedals is very tiring and a rider can soon burn himself out. But used sparingly at the right time, an experienced rider can save energy in the long run.

When deciding how to climb a hill on a bicycle, think of it as a work load. Imagine two men, each moving 100lbs. of sand from A to B in five minutes. One man hoists the 100lb. bag of sand on his shoulder, moves it from A to B in one minute, then sits down and rests for four minutes. The other man divides the sand into five, 20lb. loads and takes a minute to move each 20lb. for a total of five minutes.

Now imagine that the two men have to immediately repeat the same task over and over. Who is the fresher? The one who makes a big effort to start with, but then rests, or the man who spreads the work load over the full five minutes? A lot depends on the makeup of each individual.

Often if a road is an undulating series of short steep hills, it is often in the interest of a rider to use the speed and momentum of the descent to carry him half way up the next climb, then without shifting down, he gets out of the saddle and puts in a super human effort to keep the momentum going to carry himself over the crest of the next hill, knowing that even if this effort takes him to the point of exhaustion, he can recover on the following descent.

On a long steep climb it is different, even a long gradual climb. One must still try to keep momentum, and must occasionally get out of the saddle to boost that momentum, but a rider cannot put in those super efforts, when there are no downhill respites where he can recover.

A rider climbs out of the saddle not only to get his full weight over the pedals, but to get his body nearer his hands so he has a direct pull on the handlebars in opposition the downward thrust of his legs. Think of using an elliptical treadmill in a gym. One has to constantly move their body from left to right, so the user’s full weight is directly over the downward stroke of the paddles.

On a bike, instead of moving the body, move the bike. As the rider thrusts down on the right pedal, he pulls upwards on the right side of the handlebar. This not only puts an opposing thrust on the pedals but it moves the bike to the left, effectively using the bike as a lever.

As the right leg pushes down on the right pedal, power is transferred through the crank, chainwheel, and chain to the rear wheel. Meanwhile the bike’s frame is moving to the left and the bottom bracket, is moving upwards on the right side.

There is not just the leverage of the crank arm, but the leverage of the whole bike frame working in the opposite direction. As the pedal moves down towards the bottom of its stroke, the right side of the crank axle is moving towards the top.

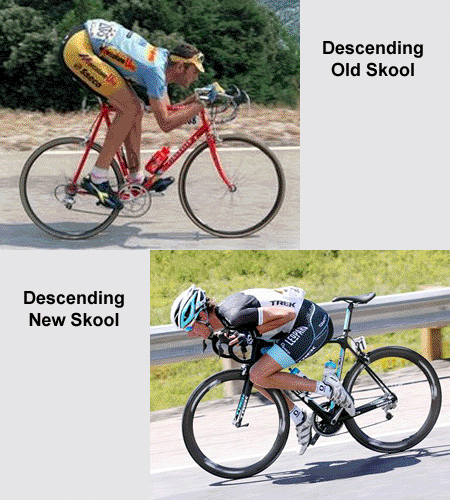

When the right pedal gets to the bottom, the rider pulls up on the left side of the handlebars, while pushing downwards on the left pedal. The rider’s body stays vertical, and the bike moves from side to side. (See top picture.) Also as the rider pushes down on one pedal, he pulls upward with his other foot on the opposing pedal.

Obviously climbing out of the saddle like this is very tiring, one is using the whole body. But used sparingly, to increase momentum, it can be very effective. For example if the gradient of a climb starts to level out, a strong rider can shift up a gear, then get out of the saddle to get the cadence back up to a level where he can sit down a pedal again.

It is all a matter of a rider knowing his fitness level, and his recovery time. Knowing his strengths and limitations, and that only comes with hard work, training and experience.

For a large selection of Sun Glasses like those worn in the picture at the top of this article, click on the link below:

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Group Riding

I saw an online question posed, “When is a group ride too big.” The answer I would give is that it is not the size of the group that is the issue, it is the makeup of the group and their collective bike riding experience and skills.

A group of 20 or even 30 professional riders, or even top experienced amateurs, might not be too big, whereas a group of six complete novices might be.

I stopped riding with my local group, because the experienced guys are just too fast for me, and the slower group has just enough people in the mix that don’t have a clue about the basic group riding skills. At best it makes the group not fun to ride with, and at worst, downright dangerous.

Probably the single most important thing in group riding is the ability to ‘Follow a Wheel.’ To draft effectively a rider must maintain a distance of no more than 18 inches from the rider ahead. Once the gap opens up to half a bike length then the following rider has no benefit from drafting.

The ideal minimum distance to follow a wheel is 6 to 8 inches. Many do not have the confidence or the skill to ride that close, so they leave a bike length, or two, or three, between each rider, as a result a group of 20 or so is strung out over a quarter of a mile, making it impossible for cars to pass the whole group without cutting in front of someone somewhere.

Others are trying to get from the back to the front of this long strung out line, the result being that there are riders two abreast in several places. Okay, so it is legal for a cyclist to pass another cyclist, but to an outsider it just appears to be an unorganized rabble all over the road. Which is pretty much what it is.

Then if the group does manage to form something that resembles a pace line, there is the rider who can’t ride smoothly, and is constantly pedal, pedal, coast. Pedal, pedal, coast. Or worse still is constantly on the brakes.

A newcomer should aim to maintain a gap of about 12 inches to start with. That way the distance can fluctuate from 6 inches to 18 inches. Try to avoid using the brakes to regulate speed, if one should find themselves getting too close to the wheel they are following, ease off on the pedaling, and pull off to one side or the other. That way the rider pulls out of the lead rider's slipstream and catches a little head wind that it will slow him down, naturally and gently.

Applying the brakes will slow the rider too quickly, and he will start to yoyo on and off. Braking opens a gap, the rider then sprints to catch up, finds himself running into the rider ahead, then has to use the brakes again and the whole cycle starts over.

This also becomes uncomfortable and dangerous for others following. Even a gentle touch of the brakes, and with the delay in reaction before the rider behind realizes what is happening. He has to slam on his brakes a little harder, and the whole effect gets magnified as it goes from one rider to the next. Often the result is someone runs into the rider ahead and brings down several riders behind him.

Don’t even stop pedaling and freewheel. This can be annoying for the following rider, better to just ease of the pressure, and keep the pedals turning at slightly less revs, just partially freewheeling.

Try to avoid overlapping the wheel in front, but if a rider should find the gap between wheels getting to be 6 inches or less, just pull off slightly to one side. Better that wheels overlap briefly than to have them actually touch.

Don’t panic, don’t use the brakes, just ease off on the pedals and let the wind the rider is catching slow him gently so he can drop back in behind the leader. The rider next in line will follow not even aware that the rider ahead changed his line slightly.

Smoothness is the key to riding in a pace line. That includes smoothness when going to the front to take your turn. Don’t sprint through and increase the speed. Gaps will open up, and cause a chain reaction down the pace line in the same way braking did, with each rider having to sprint harder and harder to close the gap ahead.

Cycling is one of the few athletic activities where one can socialize while participating. But in order to socialize one must ride in a group. With more and more new people coming into the sport all the time the situation will get worse before it gets better.

What are your pet peeves with inexperienced riders on group rides?