The Bicycle: Evolution or Intelligent design. Part I

Mon, November 24, 2014

Mon, November 24, 2014

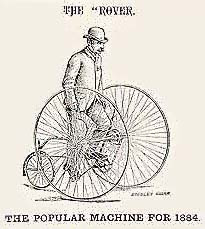

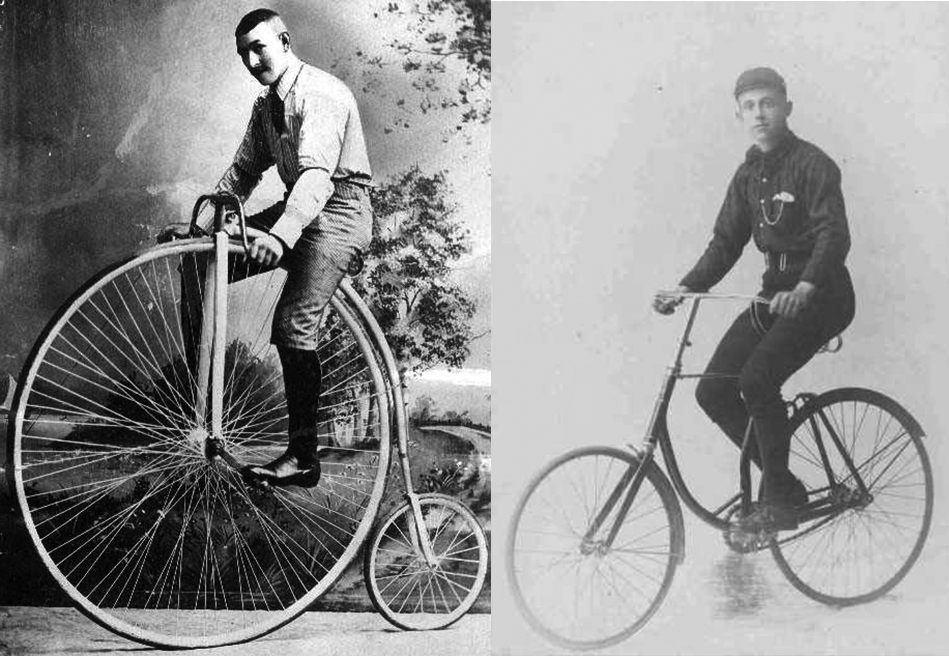

The chain driven bicycle was invented almost 130 years ago. (Picture left, The Rover "Safety" Bicycle 1885.)

The chain driven bicycle was invented almost 130 years ago. (Picture left, The Rover "Safety" Bicycle 1885.)

To the layman, or the untrained eye, this bicycle is basically the same as today’s bike.

But its geometry was directly influenced by its predecessor, the High-Wheeler. And that would influence frame design for the next 60 years. Indirectly it had an influence on what we ride today.

I have been riding bikes, racing bikes, designing and building bikes, and writing articles about bikes for 65 years, which is half of the period chain driven bikes have existed.

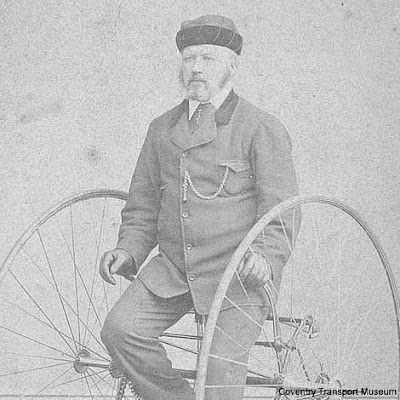

Albert “Pop” Hodge, who was my mentor, and first introduced me to the art of framebuilding, was born in 1877, and therefore witnessed firsthand the invention and early development of the bicycle. Pop Hodge was close to 80 years old when I first met him around 1953. (Picture below right.)

From what he told me, and what I have observed, back then and since, in the 130 years the bicycle has gone through a slow evolution.

From what he told me, and what I have observed, back then and since, in the 130 years the bicycle has gone through a slow evolution.

During each phase, what happened previously affected the design of the next generation of bicycles.

The title of this piece has religious overtones, because like religion, much is spoken and written about the bicycle because “It is so.”

The center of the knee shall be over the pedal. But why? Because it is written. Wise men have deemed it is so.

When I started racing in 1952, we rode bikes with a seat angle of 70 or 71 degrees. We were taught that the shin of the lower leg, should be vertical. The center of the knee was actually behind the pedal. Wise men taught us that in order to pedal fast, and efficiently, one had to sit back.

In practice I soon found this was not so. When making a maximum effort, and pedaling at maximum revs, I found myself sliding forward on the saddle, which was uncomfortable, distracting, and had the effect of the saddle being much too low.

The term “Riding the Rivet,” is still used today to describe a cyclist making a maximum effort. The term was around when I began racing in the early 1950s when saddles were leather and actually had rivets to hold the leather to the saddle frame.

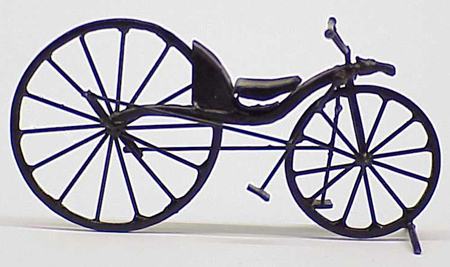

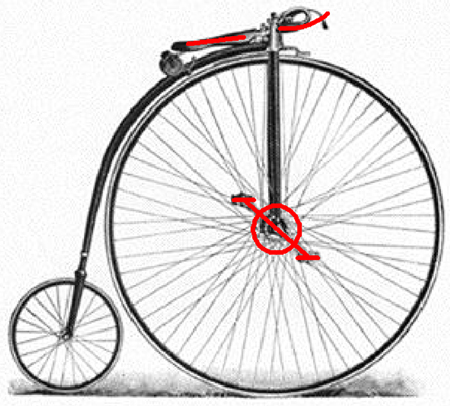

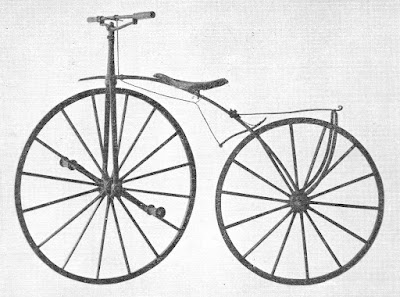

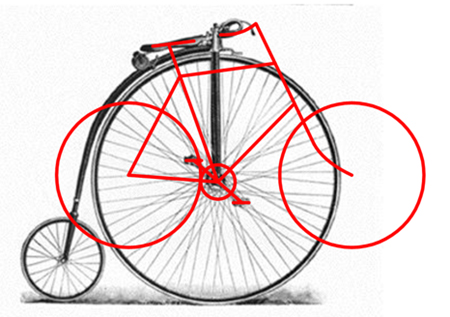

To understand why seat angles were so shallow back then, one has to go all the way back to the predecessor of the chain driven bicycle, to the “Ordinary” or Penny-Farthing bicycle. (Left,)

To understand why seat angles were so shallow back then, one has to go all the way back to the predecessor of the chain driven bicycle, to the “Ordinary” or Penny-Farthing bicycle. (Left,)

This was the first “Enthusiasts” bike. One had to be an enthusiast, as well a young, fit and agile athlete just to mount and ride one of these.

Today’s cyclist might think it a problem to make an emergency stop with their feet clipped in. Imagine making an emergency stop on a High-wheeler, and you are sitting over five feet above the ground. One had to dismount in a hurry, or fall over.

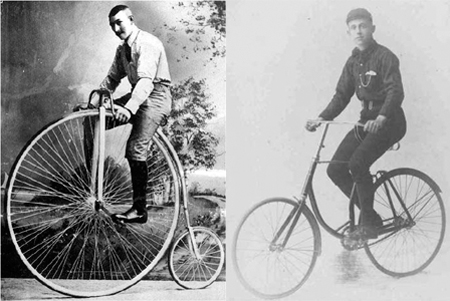

When the chain driven bike was invented in 1885 it was not immediately accepted by the enthusiast. These enthusiasts were the hard core “Roadies” of their day. The high-wheeler or Ordinary was still much faster. It wasn’t until pneumatic tires came into being in 1888 that the chain driven bike became faster and was accepted by the enthusiast.

These enthusiasts were the experts of the day, and what they learned riding the Ordinary influenced them and carried over to the chain driven bike. The Ordinary was limited by its simplicity, as to where the rider could sit, for example.

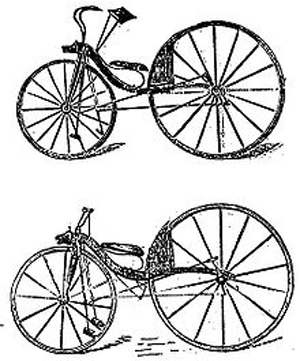

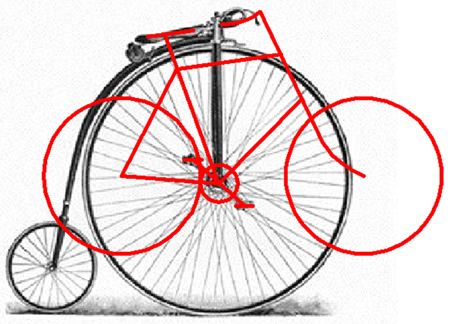

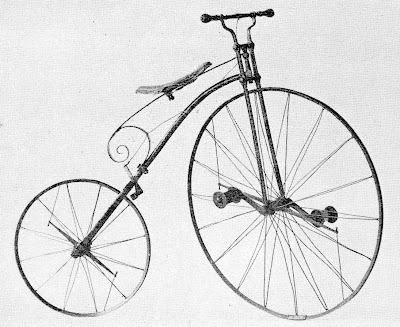

Imagine if your handlebars were directly above your bottom bracket. There would be no other choice but to sit some considerable distance back behind the pedals. When the first “Safety” or chain driven bike came into being, it was designed so the handle bars and the saddle were positioned in relation to the pedals exactly the same as its predecessor the High-wheeler. Making a seat angle of around 69 degrees. (See picture above.)

(Above.) Two different bicycles, but the exact same rider position. Note the rider's shin is vertical, a positioning "Guide" that would last another 60 years into the 1950s.

(Above.) Two different bicycles, but the exact same rider position. Note the rider's shin is vertical, a positioning "Guide" that would last another 60 years into the 1950s.

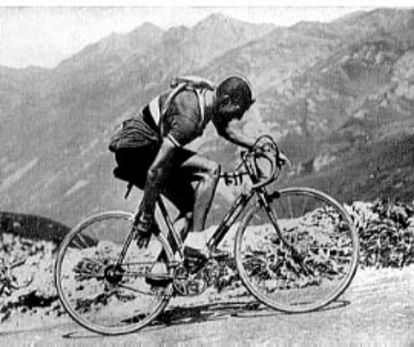

Below is a typical racing bike of the 1950s. Louison Bobet's 1954 Tour de France bike. Its shallow seat angle can be traced back to the High Wheeler of the 1800s.

A generation of “Experts” who had learned to pedal on the High-wheeler, then taught the next generation who became the following generation’s experts, and so on for the next 60 years and into the 1950s when I came along.

There was another factor that maintained this notion that seat angles shall be shallow, and an important one. This I would learn from framebuilder Pop Hodge. Frame lugs were heavy steel castings, and they were limited in the angles that were available.

It suited lug manufacturers to make their product in a limited number of angles. In later years thinner pressed steel lugs became available and it was then possible to alter an angle slightly. But not so prior to the 1950s.

73 degrees was established as an ideal head angle sometime in the 1920s or 1930s. This is still the norm today, and in the past when I have experimented with steeper or shallower head angles, I found no improvement.

Building frames with a head angle of 73 degrees, and a seat angle 2 or 3 degrees shallower, suited the framebuilder. With the head tube steeper and the seat tube leaning back away from that angle, as the framebuilder built a taller, or larger frame the top tube automatically became longer, which made the framebuilder’s job easier, and suited the taller rider.

This article is based on a talk I recently gave at the Philly Bike Expo, and will have to be written in two parts. In the next piece I will explain what happened after the 1950s. How the 73 degree paralell frame, still a popular design today, came about. The reason may surprise you.

Two main factors determine frame design, throughout history and even to this day. Experts who simply re-cycle information that was written by previous generations of experts. And framebuilders and manufacturers doing what is easiest and most profitable for them.

To Share click "Share Article" below

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |