The King: Alf Engers

Mon, December 13, 2010

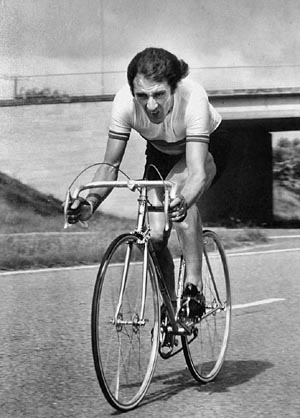

Mon, December 13, 2010  Alfred Robert Engers, better known as Alf Engers was the first British Time Trialist to record a time under 50 minutes for the 25 mile distance. (40.23 Km.)

Alfred Robert Engers, better known as Alf Engers was the first British Time Trialist to record a time under 50 minutes for the 25 mile distance. (40.23 Km.)

He did this phenomenal ride on August, 5th 1978, in a time of 49 minutes and 24 seconds. This meant that he averaged 30.36 mph (48.87 Kmph.) for the distance.

A measure of the greatness of this ride was that this record stood for 13 more years.

One also has to realize that this record was set in an era when there were no disc wheels, aero bars, skin-suits and aerodynamic helmets. Even to this day, there are only a handful of riders who can manage a sub fifty minute ride for 25 miles.

Alf Engers was no youngster when he set this record; he was 38 years old with a career that had spanned almost two decades.

Alf Engers was no youngster when he set this record; he was 38 years old with a career that had spanned almost two decades.

In fact he had originally set a new competition record for 25 miles at aged 19 in 1959, with a time of 55 minutes, 11 seconds.

He was an interesting rider in that he not only trained and prepared himself physically for his rides, but before each event he would sit quietly and meditate, to prepare himself mentally for the task at hand.

By the 1970s Engers was a “Rock Star” in the British cycling community; he was known as “The King,” and like a Rock Star, his career was not without controversy.

He was constantly “at odds” with cycling officials, mostly those in the Road Time Trials Council, which was at that time the governing body of the sport.

He was constantly “at odds” with cycling officials, mostly those in the Road Time Trials Council, which was at that time the governing body of the sport.

In the early 1960s Alf briefly turned “Independent” which was a semi-professional class at the time, where riders could ride in both amateur and pro events. However, when Engers re-applied for amateur status in 1963 he was denied, again and again, and was not allowed to compete until 1968.

When one is “hated” by officials that govern a sport, it makes it difficult when that person is so good that he cannot really be ignored.

After his come back to the sport, Alf Engers answer was to break the 25 mile record, not once, but twice the following year in 1969.

After his come back to the sport, Alf Engers answer was to break the 25 mile record, not once, but twice the following year in 1969.

Bringing the time down to 51 min. 59 sec., and later that year to 51:00.

This record stood until Alf himself broke it and put it out of reach in 1978.

Engers was constantly warned by officials throughout his career for his habit of riding down the center of the lane.

Whether he actually rode in the middle of the lane, or just a third of the way out from the edge, is not clear. This makes more sense to ride where the inside wheels of motor traffic run, where the road is smoothest, and cleanest, and there are less chances of a puncture.

In 1976 he was stopped by the police during a time trial event. He claimed he was on to a potential record breaking ride at the time. He was stopped for “riding dangerously,” and the RTTC suspended him for the rest of that season.

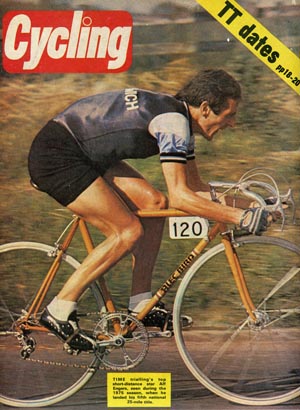

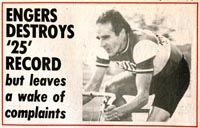

Even his sub 50 minuet record breaking ride in 1978, was marred in that the RTTC refused to ratify the record for several weeks, stating that Engers had once again, ridden dangerously by riding in the center of the lane. (See the “Cycling” headline on the left.)

Even his sub 50 minuet record breaking ride in 1978, was marred in that the RTTC refused to ratify the record for several weeks, stating that Engers had once again, ridden dangerously by riding in the center of the lane. (See the “Cycling” headline on the left.)

To understand the mindset of officials running British time-trialing during that period, one only has to look at the history of bike racing in the UK. For so many years up until the 1960s the sport of time trialing was run like a secret society, publicity was shunned, and large crowds of spectators were discouraged from attending events.

Alf Engers, with his “Rock Star” persona brought large crowds whenever he rode, and that did not fit with the establishment that was the RTTC.

Alf Engers, with his “Rock Star” persona brought large crowds whenever he rode, and that did not fit with the establishment that was the RTTC.

I never met Alf but from what I have heard, I can speculate that he most likely had a “Don’t give a shit,” attitude towards the officials, which probably didn’t help. But when one is “The King,” surely it is okay to have an attitude.

Engers was a trend setter, he was largely responsible for the 1970s craze of drilling holes in components to reduce weight, known as “Drillium.”

Another trend was “Fag Paper” clearances, where the wheel just barely cleared the frame tubes, on bikes built by Alec Bird, and Alan Shorter. (See the color “Cycling” picture near the top.)

Alf Engers set this record in spite of huge obstacles placed in the way of his career. He was banned from competing during most of the 1960s, and one has to realize these would have been his peak years as an athlete.

Most would have quit competitive cycling altogether under these circumstances. The fact that he didn’t shows the pure grit, determination, and character of the man. There is a reason they called him “The King.”

Here is a recent two part interview with Alf Engers in which he talks about that era, and his record. Here is the link to Part I, and Part II.

Here is a link to a firsthand account of the actual record breaking ride, by Gordon Hayes

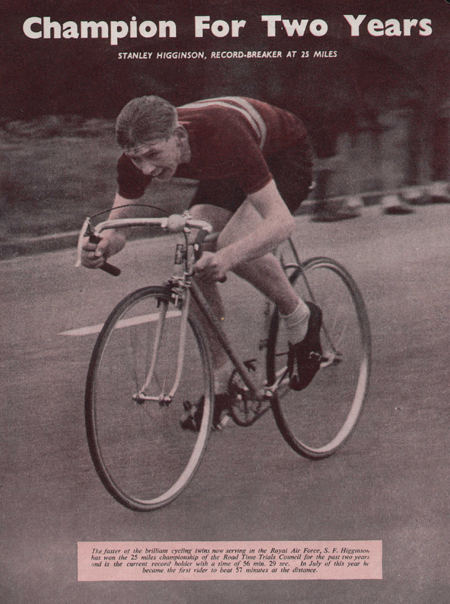

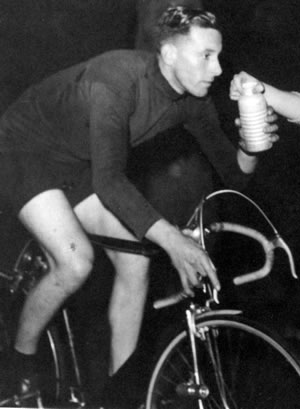

The picture above is of me riding in the National Championship

The picture above is of me riding in the National Championship