Gino Bartali: A cyclist who saved a nation

Mon, January 21, 2008

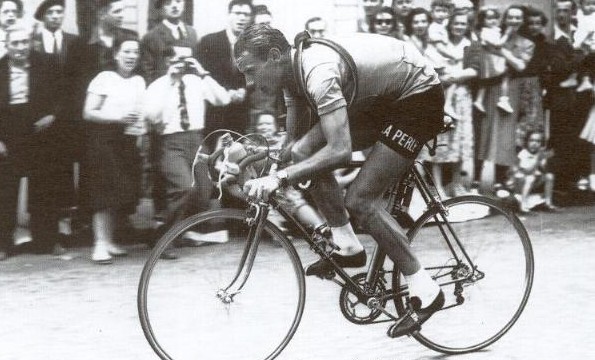

Mon, January 21, 2008  Gino Bartali born in Florence, Italy, in 1914 had a cycling career that spanned both sides of WWII.

Gino Bartali born in Florence, Italy, in 1914 had a cycling career that spanned both sides of WWII.

He was 24 years old when he won the Tour de France in 1938; then the war robbed him of his peak athletic years, from his mid twenties to his early thirties.

He came back ten years later in 1948 to win the Tour a second time. He also won the Giro d’Italia three times, in 1936, 1937, and again after the war in 1946.

Bartali was a great climber and won the Giro Mountains Jersey a record seven times. He was also the first to win both the Mountains Jersey and take overall victory in the Tour de France in 1938, then repeated the feat in his 1948 win.

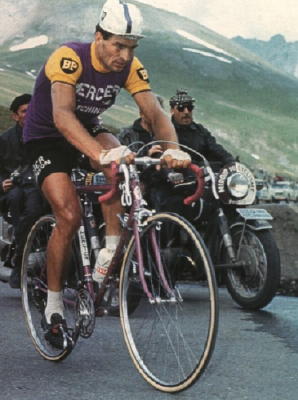

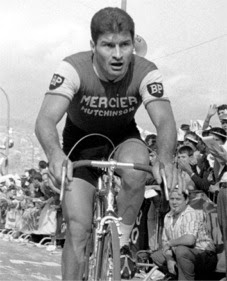

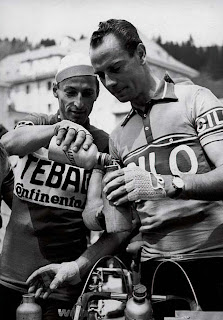

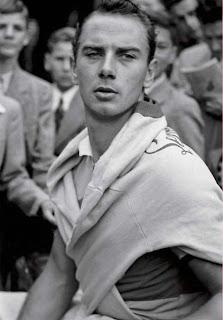

Gino Bartali is probably best known for his epic rivalry with Fausto Coppi, another great Italian cyclist. (Picture below left, Coppi nearest camera.) Bartali from Florence in the Tuscany region, was a devout Catholic and deeply religious; this earned him the nickname of “Gino the Pious.” Coppi, on the other hand, was from the industrial north, was not religious at all.

The rivalry between these two in some ways divided a nation, but both riders gave Italy much to celebrate, and this was a country that needed cause for jubilation at that time. During the late 1940s and early 1950s, Italy was still recovering their defeat in WWII, and the rest of Europe was still slow to forgive. It has been said that Gino Bartali’s 1948 Tour de France win helped subdue political unrest in Italy, even possible civil war.

It has been said that Gino Bartali’s 1948 Tour de France win helped subdue political unrest in Italy, even possible civil war.

Bartali took the yellow jersey in the first stage with a win in the finishing sprint.

In the following stages the lead was taken by Lousion Bobet, a rising young French star riding his second Tour.

Bobet emerged from the Pyrenees with a nine minute overall lead, and Bartali was some twenty minutes down.

Meanwhile back in Italy, Palmiro Togliatti, Secretary of the Italian Communist Party had been seriously wounded in an assassination attempt, which resulted in large scale civil unrest, protests, and rioting in the streets throughout Italy.

Bartali received a phone call from a friend, Alcide de Gaspari, a Deputy in the Italian Christian Democratic Party. He told Gino of the unrest back home and told him he needed him to win a stage. Such a win would distract the population from the political turmoil.

Bartali told him, “I’ll do better than that; I will win the whole race.” The next day was Cannes to Briançon, and included three major climbs, the Allos, Vars and Izoard. It took Bartali just ten hours, nine minutes and twenty eight seconds to cover the 274 kilometers, (170 miles.) crossing the three mountain passes with a total climbing amount of over 5300 meters. (17,388 feet.)

It was more than six minutes when the second rider came in. When Bobet finished, in twelfth place, over eighteen minutes had passed, and Bartali was now second overall, just 1min. 6sec. behind his young French rival.

This was only the beginning of Bartali’s softening up process; he dominated the race the following day. Major climbs, over the Col du Galibier and the Col de la Croix de Fer before a final attack on the Col de Porte saw him finish in Aix-les-Bains once again six minutes ahead of his nearest rival. Bobet's tenure on the Yellow Jersey was over; Bartali now led by over eight minutes. Stage 15 to Lausanne, and Bartali was again a solo victor; he was totally dominating the race. Gino Bartali had gone from twenty minutes behind in Cannes, to an overwhelming lead of 32 minutes. He lost time in later time-trail stages but still came away the clear winner by 26 minutes at the end of the Tour.

Stage 15 to Lausanne, and Bartali was again a solo victor; he was totally dominating the race. Gino Bartali had gone from twenty minutes behind in Cannes, to an overwhelming lead of 32 minutes. He lost time in later time-trail stages but still came away the clear winner by 26 minutes at the end of the Tour.

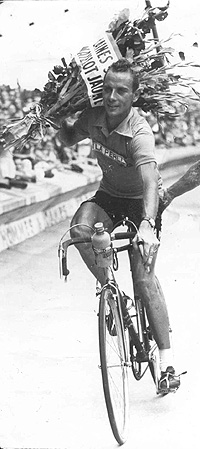

Winning a total of seven stages, Bartali won with one of the most dominant displays ever seen in the Tour de France.

The population of Italy watched enthralled and by time Bartali arrived victorious in Paris, the political heat in that country had noticeably cooled.

De Gaspari's instincts had been right, Bartali had won the Tour, and in doing so, provided a distraction from his country’s political unrest. Never can a race have mattered so much. It wasn’t until after his death that his family discovered he had been a member of the Italian Resistance movement during WWII, and was instrumental in helping Italian Jews escape to safety from German occupied Italy.

It wasn’t until after his death that his family discovered he had been a member of the Italian Resistance movement during WWII, and was instrumental in helping Italian Jews escape to safety from German occupied Italy.

He used his fame as a racing cyclist to act as a courier; the authorities knew who he was and let him come and go as he pleased.

On his training rides, he would smuggle forged documents, hidden on his bike, to and from various convents where the Jewish fugitives were hidden.

In later years, Gino Bartali only mentioned these episodes to his sons in passing. It wasn’t until after his death when researching his diaries for a biography was the full extent of his war-time resistance involvement revealed. A movie was later made about these exploits, but as far as I know, it has not been shown outside of Italy.

The latter years of Gino Bartali’s career were somewhat overshadowed by a younger Fausto Coppi. (Whom I will write about later.) However, I have touched on the earlier part of his career before Coppi came into his own, in the hopes of showing he was a great rider in his own right.

He was another of my cycling heroes from my youth; turned out to be a real life hero and a great deal more than just another cycling legend.

Additional picture source: Tiscali.it, and La Repubblica

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |

Dave Moulton | Comments Off |